Of the Wrong Place, Wrong Way Looking

"If I don’t do it, the person I hate the most will."

This raw, visceral logic is at the root of most of game theory’s most haunting lessons. It captures the blunt logic of rivalries: not every action is measured in profits, but in the impossibility of letting someone else seize the advantage. It is a logic of necessity, of survival, of securing a position in a future that is arriving with unnerving speed. Doubts about AI’s economic reality — the latest triggered again by a much-discussed MIT study — follow a familiar cycle. Markets shiver, headlines ask whether the bubble has burst, and analysts glance nervously at financial statements that do not yet glisten with profit. But this is the wrong lens. To doubt that AI is real is to miss the most obvious fact of our age: the change is everywhere, and one must be almost willfully blind not to notice it. Societies, workflows, consumption patterns, and habits are mutating in every corner of the world, reshaped by tools that did not exist two years ago. Even ROI lags only if viewed narrowly, while utility is omnipresent.

The way we write has changed, the way we read has changed, the way we create and consume the torrent of content that defines our age has changed. Our images are no longer just captured but conjured, our videos edited and generated by unseen hands. Our second opinions come from digital doctors, our professional services are under siege from automated expertise, our programmers are augmented by machine partners, and every application on every device throbs with a new, predictive intelligence. The very landscape of the internet is being terraformed, its traffic patterns rerouted by AI agents. AI is changing drug discovery, enabling robotics, driving vehicles, and helping us understand all forces of nature. At GenInnov, we see the birth of the fourth macro sector, although economists may not add that in the GDP fragments for years. The integration is too deep, the momentum too vast. The old world is not just disappearing; it is already gone.

The Squeezed Middlemen: The Application Layer

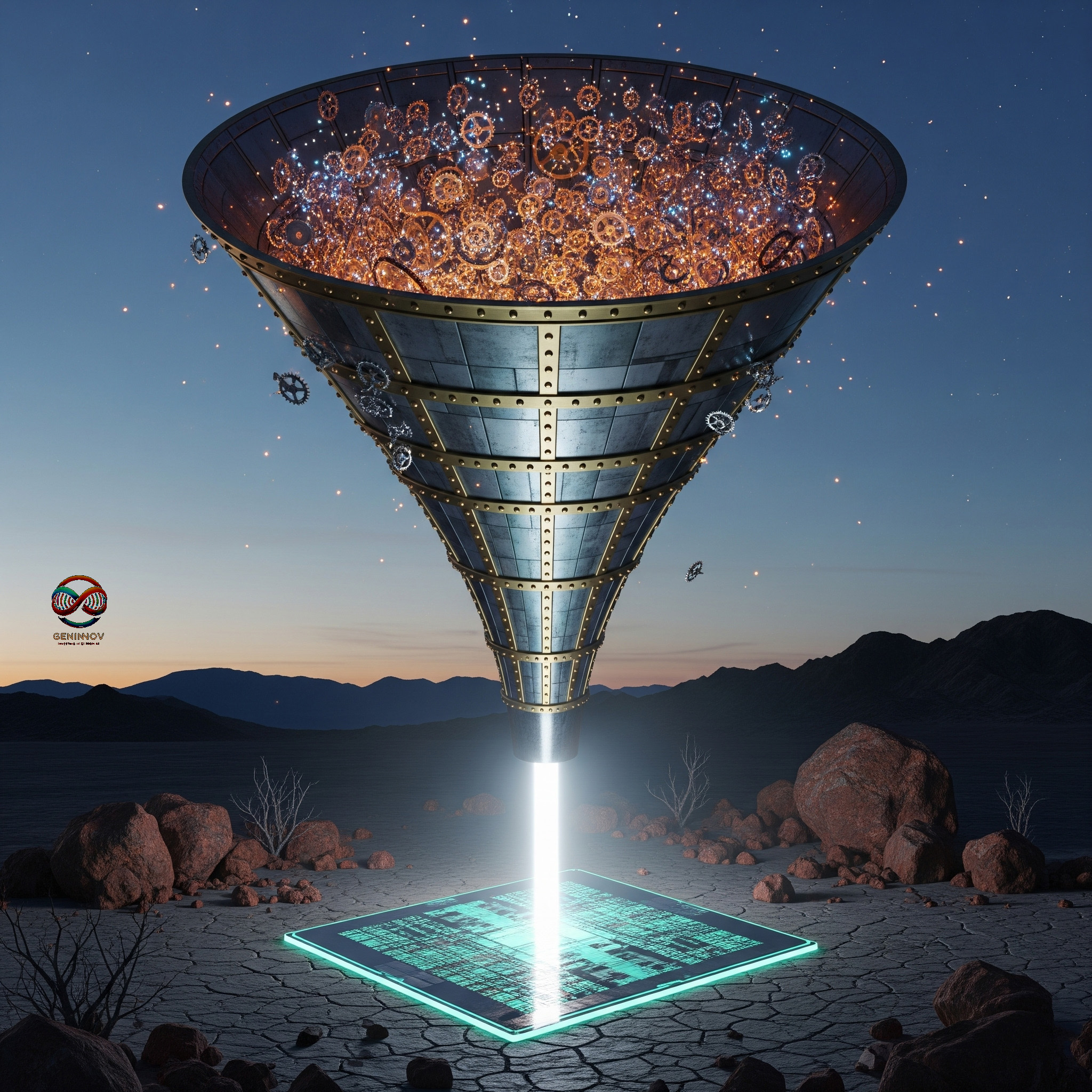

Herein lies the paradox. There is massive, undeniable consumer utility. There is massive, undeniable corporate utility. The frustration over a lack of returns stems not from a lack of value, but from a habit of looking for it in all the wrong places. A myopic gaze fixed on the wrong horizons. Habitual investors and analysts, conditioned by past paradigms, scrutinize the application layer where value once pooled, oblivious to its evolution into a mere conduit. Today, the true spoils accrue upstream: in the forges of data centers humming with energy, cloud services scaling infinities, GPUs churning computations like modern alchemists, semiconductor fabs etching the future onto silicon wafers. Today’s middlemen, including app developers, AI/agent creators, and workflow integrators, have become the funnel collecting the riches from value-deriving consumers to these upstream titans, with their margins squeezed in the process.

To fixate on the profitability of this disrupted middle segment is a profound category error. It is akin to assessing the transformative power of the internet by scrutinizing the balance sheets of bookstores and VCR manufacturers in 1995. It is an analysis focused squarely on the carnage of disruption, mistaking the turmoil of a paradigm shift for a failure of the paradigm itself. The profits are real, and the ROI is staggering; it is simply accruing to a new industrial layer. The more urgent question, then, is not whether AI is paying off, but why so many brilliant minds and ambitious companies in this turbulent middle layer continue to innovate so fiercely, acting as this essential funnel. The reasons are numerous, complex, and reveal a new calculus for value in the modern age, a calculus that extends far beyond the following quarterly report.

The New Calculus of AI Investment

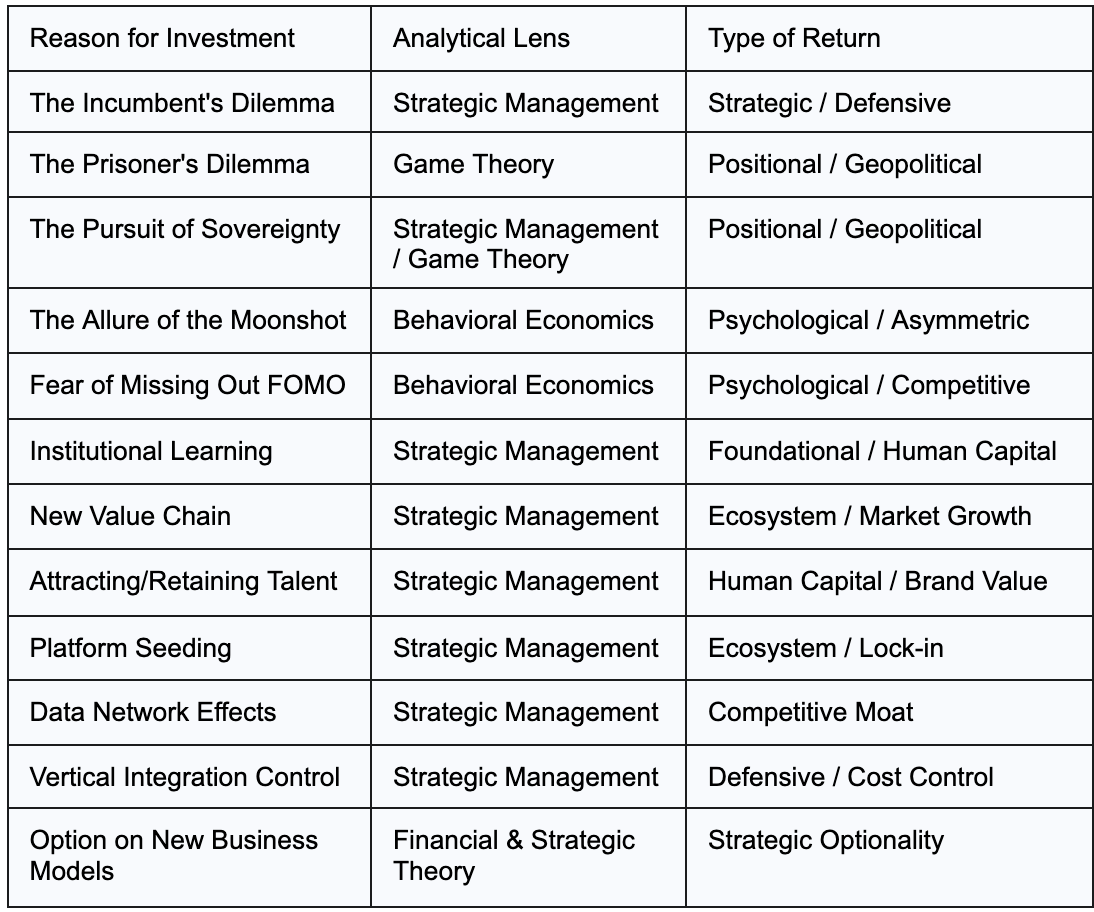

To be fair, the MIT report spooking the market is far more than the highlighted headline that “approximately 95% of generative AI pilots fail to deliver measurable financial impact, with only 5% achieving rapid revenue acceleration.” This note is not a counter to their findings, but rather a list of motivations driving investment in AI for those concerned about investments. To understand the motivations driving investment in AI, even for those not seeing the returns, we must look beyond traditional financial metrics. The following framework outlines the strategic, competitive, and psychological rationales compelling entities to invest as a matter of survival and future positioning.

1. The Disrupt-or-Die Defense

The logic here is brutal and simple: invest to avoid being wiped out. New, AI-native entrants can replicate a legacy company’s core service at a fraction of the cost, making inaction a form of corporate suicide. Adobe’s aggressive integration of its Firefly generative AI is a perfect example; it was a necessary defensive maneuver against agile challengers like Midjourney that threatened to make Photoshop obsolete. This reflects the desperate e-commerce investments made by Barnes & Noble in the late 1990s: a costly, ultimately insufficient, but non-negotiable attempt to survive the Amazon onslaught.

2. The Arms-Race Deterrence

In a competitive market, if one rival adopts a technology that fundamentally lowers their cost curve, every other player must follow suit simply to stay in the game. The gains are often passed to the consumer, resulting in little net profit for the industry, but the cost of being the lone laggard is extinction. In global shipping, Maersk and CMA-CGM both rolled out AI-powered optimizers that cut fuel costs, a benefit that flowed to shippers, not their bottom line. Neither could afford not to invest. This mirrors the 1970s, when U.S. automakers had to introduce many new products and features to compete with Japanese efficiency, even as they were losing market share and not making money.

3. The Geopolitical Prisoner’s Dilemma

On the world stage, AI investment is not about profit but about power. The dynamic between the United States and China is a classic Prisoner's Dilemma: while global cooperation on AI safety might produce the best collective outcome, the fear that the other side will gain an insurmountable advantage forces both nations into a costly technological arms race. The U.S. implements export controls on advanced chips to slow China, while China invests massively in sovereign capabilities to chart its path. The "return" is not financial; it is the avoidance of the worst-case scenario: a catastrophic loss of global power. And, the realization is not just with the US and China but with all the major powers.

4. The Pursuit of National Sovereignty

For nations outside the traditional superpowers, AI investment is a tool for securing geopolitical relevance and economic diversification. The Gulf nations, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are pouring billions into sovereign AI funds and data centers, not to beat the U.S. or China at building foundational models, but to make themselves indispensable nodes in the global AI apparatus. By providing land, funding, and infrastructure, they secure a form of strategic influence once derived from oil, ensuring they have a powerful seat at the table in the 21st-century economy.

5. The Talent Magnet

In a knowledge-based economy, the most valuable asset is human capital. Investing in cutting-edge, high-profile AI projects is one of the most powerful ways to attract and retain scarce elite talent. Many software giants and LLM makers, despite no hope of near-term returns, continue to fund fundamental AI research labs, not always for direct product outcomes, but to create an environment where the world’s best minds want to work. This was the same logic behind Bell Labs in the 20th century, which subsidized pure physics research to attract world-class scientists whose work later became the foundation of the digital age.

6. Institutional Learning and Capability Building

Many AI projects that are financial failures are crucial investments in institutional knowledge. The real return isn't profit, but building an "AI muscle" or the internal expertise, data infrastructure, and culture required to compete in the future. For instance, Alibaba’s massive investment in cloud and AI infrastructure is designed to build an enduring "technological moat". This is a modern parallel to Toyota’s early, experimental work on "just-in-time" processes in the 1950s, which initially seemed inefficient but contained the seeds of its future global dominance in lean manufacturing.

7. The Venture-Style Call Option

SoftBank’s $40 billion bet on OpenAI was not rational in quarterly terms. Nor was the $2 billion raised at a $12 billion valuation by an AI startup with no product. These are asymmetric bets. Behavioral economics calls it the moonshot bias: the willingness to take losses on 99 projects if one defines an era. Railroads, electricity, the internet — all required such “irrational” moonshots.

8. Platform Seeding and Ecosystem Lock-In

Sometimes, the goal of an AI investment is not to make money from the AI tool itself, but to use it as a loss-leader to lock users into a broader, profitable ecosystem. Shopify offers free AI image-generation tools to its merchants; the tools themselves lose money, but they drive more sales, which feeds Shopify’s high-margin payments business. Google’s DeepMind solved the 50-year-old protein folding problem with AlphaFold; while it generated no direct revenue, it gave Google a foundational position in the emerging field of bio-AI. This is a classic strategy, famously used by Microsoft when it gave away or bundled Internet Explorer to cement the dominance of its Windows operating system, creating an ecosystem that generated massive profits for decades.

9. The Data Moat

In the 21st century, proprietary data is one of the most formidable competitive advantages. Many AI applications are designed less for their immediate function and more for their ability to generate unique data that improves the AI in a virtuous cycle. Tesla’s investment in its Full Self-Driving program is a prime example. Despite regulatory hurdles and high costs, every mile driven by a Tesla vehicle feeds its models, creating a data asset that is nearly impossible for competitors to replicate. This was Google’s original advantage: its search engine collected data on user intent that made its algorithm unbeatable.

10. Vertical Integration for Cost Control

As AI becomes central to business operations, relying on a single upstream provider for foundational models becomes a major strategic risk. Companies invest in building their own AI, even at a higher initial cost, to avoid being squeezed on price by a monopolistic vendor in the future. Bloomberg developed its large language model, BloombergGPT, at great expense. The motivation was not to sell it, but to avoid being dependent on a third-party model provider who could later charge exorbitant fees for processing sensitive financial text. This echoes Netflix’s decision to build its content delivery network to stop paying massive fees to Akamai.

11. The FOMO Spiral

When 75% of US AI deals include corporate venture capital, it is not ROI but fear at work. Siemens, Samsung, Dow, and private equity funds pour money into it because the nightmare is watching a rival secure a transformative partnership. FOMO becomes rational: to invest is to avoid irrelevance. The “return” is not gain but protection against extinction.

12. Creating Positive Externalities

India’s AI Centers of Excellence in healthcare, agriculture, and education are not about profits. They are about seeding entirely new industries. Governments create ecosystems, infrastructure, universities, startups, and then step back as communities benefit from the creation of positive externalities. The “return” is national competitiveness. It is a bet that talent and ideas, once catalyzed, will compound into industries no balance sheet can yet tally.

13. Shaping Industry Standards

The company that defines the technical standards for an emerging industry often becomes the long-term winner. NVIDIA’s decade-long investment in its CUDA software platform is a masterclass in this strategy. They invested heavily in developing the software layer for their GPUs well before the AI boom, establishing it as the de facto standard for AI development. This effectively locked an entire generation of researchers and developers into their ecosystem, ensuring their dominance in AI hardware was nearly unassailable. Efforts to shape industry standards are costly and typically require years of investment with no immediate returns.

14. The Signal to Capital Markets

In public markets, narrative can be as valuable as earnings. Announcing a significant AI initiative can signal future growth potential to investors, leading to a higher stock price and a lower cost of capital, even if the project is expected to dilute margins in the short term.

Conclusion: Redefining the Scoreboard

The anxiety over AI’s return on investment is not entirely unfounded, but it is dangerously myopic. It judges a tidal wave by the standards of a swimming pool. The evidence is clear: AI is already generating immense utility and reshaping the global economy. From accelerating drug discovery and optimizing global supply chains to transforming creative expression and augmenting human intellect, its impact is profound and irreversible. The disconnect arises from a failure to see that the profits of this revolution are not missing; they have simply moved. They are flowing upstream to a new foundational layer of the economy, comprising the makers of chips, the builders of data centers, and the providers of cloud services. The final makers of AI products and services add tremendous value as well, but intense competition and ongoing disruption have reduced their ability to hold on to the gains.

The frustration of venture capitalists, application layer stakeholders, and the followers of legacy industries’ AI efforts is the understandable pain of disruption. In this new landscape, business moats that once seemed permanent have evaporated. As competition in areas like image generation, coding assistants, and automated agents intensifies, value accrues not to the producers of these services but to the consumers who benefit from their proliferation and the upstream giants who supply their computational power. To declare this a "bubble" because profits are not appearing where they have historically is to fundamentally misread the nature of the shift, in our mind.

So, as much as we expect USD600bn questions like concerns on the AI’s ROI to recur every few months, with occasional sharp and extended global investor pessimism, we expect the irreversible, global change that is afoot to keep reinforcing the far more important and powerful reverse arguments.

The real returns for societies, communities, corporates, and even individuals are not always commercial. There could be many others as discussed above, which is anything but an exhaustive list. As the late Clayton Christensen taught us, disruptive technologies always underperform on the metrics of the old world until they redefine the scoreboard entirely. For many, investing in AI while the traditional ROI flashes red is, paradoxically, the price of admission to whatever scoreboard comes next.