Should we Simply Say “Super-Cycle” and Be Done?

When one surveys the general commentary about memory makers and their current profitability surge, the overwhelming impression is that these companies are simply lucky to be in the right place at the right time. The narrative, particularly of many befuddled experienced experts, almost suggests that these are undeserving beneficiaries of circumstance, that their windfall has little to do with what they have done or continue to do, and that it is merely a function of very high demand. The commentary around these companies betrays an assumption of extreme simplicity in their managerial decision-making. Whatever success they are experiencing, we are told, will evaporate as soon as the cycle turns or these companies, due to their inherent naivety that only they do not understand, build capacity nobody would want. It is just a matter of time.

Effectively, these firms are depicted as rivals in a zero-sum game. The start of 2025 provided an amusing case study in this thinking. Every time rumors emerged that Micron or Samsung had made progress in developing their high-bandwidth memory and might receive qualification from major buyers like Nvidia, the stock prices of all three memory makers would come under pressure. The implicit assumption was clear: the world that can comfortably accommodate tens of thousands of cafes with pricing power and perhaps a couple of dozen chip design companies is somehow too small for three memory makers. The market behavior suggested that these companies exist in a perpetual blood feud, as we have written before, caring nothing for profitability and everything for market share. Once they all start making similar products, the assumption goes, they will inevitably slash prices to the bone and destroy each other's margins because, well, that is what simpletons do.

Now, as prices rise at rates nobody forecast at the beginning of the year, 3-5x for even the lowly DDRs, this perspective persists. Nothing is attributed to management decisions. The profitability is treated as an accident of supply and demand forces beyond anyone's control. This lazy thinking needs to stop. The reality of 2025 is that the memory industry is being steered by some of the most disciplined, ruthless, and arguably brilliant management decisions in recent history—decisions that have completely broken the old models. This framing has profound implications for how we think about these companies as we move into 2026.

A Brief Detour: The Pricing Revolution Nobody Discusses

Before we get to the memory companies specifically, it is worth noting that something fundamental has changed in how corporate management globally thinks about pricing. As we explored in our piece on the Notionality of Nominal Growth, we now live in the world of hardly any “sale” signs, where more and more sectors have stopped seeing market share battles through price wars, and where the main reason why doomerism does not come to a pass is that nominal growth remains high.

The period from the early 1990s until roughly 2022 was characterized by a particular orthodoxy. Pricing decisions, which are policy choices unlike costs that are real, were subordinated to long-term customer relationships and market share accumulation. This was the era of Harvard Business School case studies, of Jack Welch-style management thinking, of the primacy of scale. Companies would tolerate margin compression to preserve customer goodwill and lock in volume.

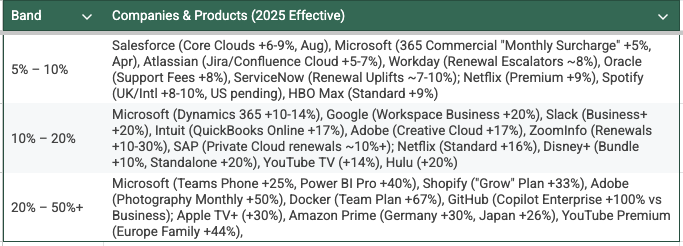

That world disappeared in 2022. Now we see price increases across industries globally, even where volumes are declining. Software and SaaS companies facing user growth headwinds raise prices by double digits. Streaming services with no supply constraints whatsoever implement annual increases of 15-20%. Even in competitive industries with overcapacity, companies hold the price line rather than run sales promotions. The shift is stark and measurable. Consider the recent quarter, where 80% of S&P companies beat earnings estimates. The beat came from the top-line growth and margin expansion, which came from pricing discipline.

The table below captures a sample of this new reality. These are price increases implemented in 2025 across technology products and services, primarily in the United States, at a time when nominal GDP growth in most developed economies runs at 4-5%.In many ways, the pricing power flex is a global phenomenon, irrespective of headline inflation numbers or central bank commentaries!

2025 Price Increases: Selected Technology Subscription-like Products

This is pricing behaviour as policy, not as reaction. It is an assertive shift away from volume maximisation toward deliberate price realisation. The question is whether memory companies are displaying similar strategic thinking.

TSMC and the New Economics of Scarcity

If companies with volume pressure are raising prices, it stands to reason that firms with both rising demand and constrained supply would do so even more assertively. TSMC provides a useful example.

On paper, same-node pricing appears to rise at single-digit percentages annually. The reality is more complex. Most of TSMC's largest and highest-paying customers are continuously migrating to more advanced nodes. The cost of producing similar products increases by an estimated 30-40% on a per-wafer basis with each node transition, based on various industry estimates.

This baseline pressure is only part of the story. What often gets overlooked is the dramatic escalation in advanced packaging. TSMC's CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) technology, essential for integrating high-bandwidth memory in AI accelerators, has seen prices rise by more than 20% in the past year due to capacity constraints, and this is only accelerating based on the newsflow of the last few weeks.

Then there is the less discussed mechanism borrowed from ride-hailing companies: surge pricing. TSMC offers what the industry calls "Super Hot Runs" (SHR), allowing customers to pay premium rates to jump the manufacturing queue. These priority access arrangements can command premiums of 40% or more above standard wafer pricing. For customers racing to validate designs or secure production slots, this has become a necessary cost of doing business.

What emerges is a picture of deliberate management decisions leveraging demand-supply dynamics. Nobody seriously disputes that TSMC's pricing reflects astute business judgment. The company holds 70% of the global foundry market, its advanced nodes are sold out for the foreseeable future, and its customers have limited alternatives. Analysts credit TSMC's management team with strategic vision. The same analysts, curiously, rarely extend this framework to memory makers.

Memory Companies: The Decisions That Changed Everything

There is almost no valuation respect afforded to memory companies, as evidenced by stock prices. Despite SK Hynix achieving returns on equity at the 40% level, the stock trades at a single-digit PE multiple (no typo). It becomes even more weird: when the interest in the stock rises, like at present, its regulators in Korea become concerned, the way almost no regulator in any market has become concerned for any stock anywhere for a while. Part of this disconnect stems from how rarely anyone writes about the genuinely interesting management decisions these companies make. Some of the decisions made this year by memory companies are arguably more significant than business decisions made anywhere else in the semiconductor space. Until people begin evaluating memory companies based on actual management choices rather than simplistic supply-demand projections and weekly spot price charts, the segment will remain misunderstood.

The most impactful management decision of 2025, which we wrote about when it occurred, was the coordinated closure of DDR4 capacity. This decision was entirely out of sync with historical patterns, and yet its massive significance was almost entirely overlooked in almost every corner of the industry. Three memory companies, supposedly locked in a blood feud as we love to keep describing the others’ impressions as, all announced capacity closures for DDR4 production within weeks of each other. They executed a monumental, voluntary decision with no external pressure or regulatory coordination, and the impact should have been as evident as it was immediate. In six months, DDR4 prices have risen multiple times, creating supply pressure for nearly every major technology company globally and delivering substantial benefits to the bottom lines of all three memory makers. Yet even in hindsight, this decision receives minimal discussion, with every success owed to the cycle that has now become a super-cycle. Because it is not being analyzed for the strategic foresight it demonstrated, people continue to underestimate the very different ways these companies are now operating.

All three behave distinctly from their supposed historical patterns. Both Samsung and SK Hynix have repeatedly stated publicly that they will not increase capacity simply to match expected demand. Their focus, they emphasize, is on return on equity. In its November Corporate Value-up plan update, the company, which is tasting the fruits of positive cash flow for the first time in years, maintained its stated "mid-30% capital intensity benchmark" but clarified that the realistic target remains 30% or below, explicitly prioritizing supply-demand optimization over aggressive capacity expansion. SK Hynix outlined a shareholder return policy tied to the generation of accumulated free cash flow rather than revenue targets.

In November 2025, Samsung's DS division reiterated plans for "measured" capital expenditure growth, explicitly linking investment decisions to margin sustainability rather than market share targets. These are not the statements of companies engaged in a race to the bottom. Their new ways are partly a reflection of the value-up drive, recognising the power of their innovations and global macro behaviour shifts around price increases, and the most important change of all: HBM is not a commodity sold in general markets! More about that below.

Samsung has made fascinating tactical moves as well, reallocating some production capacity away from HBM toward DDR5 to exploit the profit arbitrage created by the rapid appreciation in DDR5 prices. Meanwhile, Micron, often viewed as the more rational player, announced its smallest planned capex increase in a decade relative to revenue growth. In December, Micron also announced it would exit the "Crucial" consumer memory business entirely. No more fighting for pennies on gamer RAM. If it’s not Enterprise or AI, Micron isn't interested.

Perhaps most striking was the joint announcement by Samsung and SK Hynix of their letters of intent with OpenAI on the same day for prospective HBM supply tied to the Stargate infrastructure project. For two companies supposedly unable to occupy the same room without attempting mutual destruction, this coordination was extraordinary.

The broader context matters. The number of companies making advanced chips is increasing. The number of data server manufacturers is rising. But the number of memory makers remains exactly three. They are the sole suppliers of advanced memory across the entire computing ecosystem, occupying a position analogous to TSMC in the foundry space. Memory's role in AI hardware is arguably as critical as processing power itself, if not more so in specific architectures. As we move into 2026, the industry would benefit from treating these companies as the strategic actors they have proven to be, rather than as automatons helplessly responding to market forces. That will require, at minimum, understanding and appreciating their management teams as seriously as we do with TSMC or Western chip designers.

Let’s Applaud Memory-Makers For Once

Of course, it is far too presumptuous to claim any authority in awarding a "business decision of the year" prize. What do we really know? Countless decisions are made across the global economy, and we observe only a sliver of them. But it is the festival season, and perhaps a bit of advocacy can be excused. What strikes us most is that nobody in the commentator community ever credits Korean memory companies with either management capability or innovation. Why else would stocks with this growth trajectory and these returns on equity trade at not even low-teen multiples? Why else would increased interest in their stocks prompt regulatory concerns? We thought it worthwhile to show some support for a sector whose analysts assume is perpetually doomed to fail.

We are not surprised that SK Hynix is considering an ADR listing, likely to find better price discovery. We discussed how Samsung should be attracting strategic investor interest in a recent note. In an otherwise nationalistic economy, the treatment of its biggest innovators, meted out without any contrary opinion in the stock market, is particularly baffling.

There is, naturally, a possibility that we are entirely wrong in our reading of these companies' management. Perhaps they remain price takers, just as the global commentariat insists. Perhaps the DDR4 capacity closure was merely a fortunate coincidence rather than the coordinated strategic maneuver it appeared to be to our jaundiced eyes, which would explain why so few bother discussing such a consequential decision. Perhaps supply will materialize from nowhere, or demand will collapse only for memories. At the same time, all else of the world economy would continue to make merry, and prices would crater as predicted for years. The real world owes nothing to anyone.

But whether fluke or foresight, the DDR4 capacity decision made by three memory makers earlier this year stands as one of the most impactful decisions in the semiconductor industry in 2025. The decision was not only immensely consequential but also revealed a mental shift that remains barely acknowledged by those who ostensibly cover the sector closely.

Perhaps it is time for at least some observers to discuss the memory industry using vocabulary beyond "cycle" and "super cycle," terms that have become almost patronizing in their reductionism. These are not companies making simple products or executing simple strategies. They simply are not recognized for the complexity of what they do.