Possessed by the Ghosts of the Bazaar

For those of us who have followed the semiconductor industry for what feels like several geological epochs, there are certain truths we hold to be self-evident. The sun rises in the east, water is wet, and the great Korean memory makers, SK Hynix and Samsung, are locked in a theological blood feud, a "War of the Roses" so deeply ingrained in their corporate DNA that their sole purpose on this earth is not to make profit, but to make the other’s life miserable.

This is the sacred scripture of the analyst community, a gospel passed down through generations. According to this holy text, these two giants, who, along with Micron, form one of the world’s most unshakable oligopolies in one of the most technologically demanding industries requiring intensive capital known to humankind, are not rational economic actors. Oh no. They are more like the Hatfields and McCoys of the silicon world. They are Manchester United and Manchester City, forced to share a city but destined to forever despise each other. Their strategy, we are told, is simple: the moment one achieves a sliver of a technological edge, it will not use it to improve margins. Instead, it will immediately weaponize it, slashing prices to oblivion in a glorious, profit-immolating blaze aimed at scorching its rival’s market share.

Of course, this lore has its roots in a bygone era, a time when memory chips were indeed slung like sacks of potatoes in the sprawling electronics bazaars of Asia. The ghost of this open marketplace, a vibrant, chaotic scene with dozens of vendors hawking their wares and haggling over pennies, still haunts the collective imagination. It matters little that today’s High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) is about as similar to that old DRAM as a modern AI GPU is to the graphics cards of yesteryear. We all remember when those graphics cards were also off-the-shelf commodities, sold in electronics markets from Hong Kong to California. Yet, no one today would dare equate a data center GPU with a simple component to be bought by the pound; that respect has been earned. Somehow, this same courtesy, this basic acknowledgment of profound technological evolution, is not extended to HBM. No matter the proof of pricing power, explosive volume growth, or the technological moats that are nearly impossible for new players to cross, the ghosts of the bazaar must be honored.

This narrative has proven immune to contradictory evidence. It’s why SK Hynix, a near-monopolist in the HBM that fuels the AI revolution, can have triple-digit revenue growth and an 18-month backlog, yet still trade at a single-digit P/E multiple. It’s how analysts can forecast a near-zero growth cliff and justify downgrades with a “historic high” price-to-book ratio, proving that for memory makers, odes are only written as eulogies.

And so, we trundled along, accepting this bizarre worldview as the natural order of things. Then, this week happened.

The Gravity of a $100 Billion Handshake

The announcement is so gobsmacking, so utterly subversive to the established dogma, that we must set aside our tone for a moment and get serious. OpenAI signed letters of intent (LOIs) with Samsung and SK hynix for prospective HBM supply tied to its ambitious Stargate AI infrastructure project. It's crucial to understand what this is and what it isn't. These are LOIs, which are materially weaker than binding, multi-year take-or-pay contracts. This is a statement of intent, and the final outcome could eventually be a small fraction of the best-case scenario. The ambition, however, is directional: to support a project with a stated goal of $500B by 2029 and a potential scenario demand of up to 900,000 wafers per month as Stargate expands. Once again, this is a scenario guidance figure, not a locked-in purchase schedule.

To grasp the sheer magnitude of this agreement, consider the context. The best-case target of 900,000 wafers per month is more than double the current global HBM capacity. SK Hynix, the dominant market leader with a 60-70% share currently, is projected to have HBM revenues of approximately $15-20 billion in 2025. If we expect no change in prices for years, this best-case scenario OpenAI take-up could imply the incremental demand in excess of $70 billion over the next four years. Factoring in production scaling and pricing premiums for advanced memory, the total value of the deal could realistically fall in a range of $80-120 billion.

For emphasis: it’s crucial to remember this depends on a cascade of non-guaranteed variables: the LOIs converting to firm orders, volatile memory ASPs, and manufacturing throughput for both memory and packaging. Still, the ambition outlined in these LOIs could represent a value more than twice the entire projected 2025 HBM revenue of the two largest producers combined. this single deal’s value could therefore be more than twice the entire projected 2025 HBM revenue of the industry. And yet, we can already hear the gears turning in the minds of memory veterans, who will no doubt find a way to frame this multi-year, industry-defining windfall as a temporary blip that marks the peak of the cycle.

The Smartest Kid in the Room Buys… Commodity Rice?

The first, most glaring question is one of location. OpenAI, the organization at the absolute epicenter of the generative AI boom, the company with a direct line to the future, decided to secure its most critical long-term supply not in GPUs, not in networking, but in the one sector the market has long dismissed as a cyclical, commodity-driven knife fight.

Why? Why would a company with arguably the cheapest access to capital on the planet, a company that thinks in decades, make its first landmark, multi-year supply play in a field supposedly defined by suicidal price wars and fleeting advantages? This is like watching a Michelin-starred chef make a public, long-term commitment to securing a specific brand of… salt.

Why Invite Both Coke and Pepsi to the Same Party?

This brings us to the deal’s second, even more baffling feature: its structure. Standard-issue corporate ruthlessness dictates that when you are the world’s most important customer, you do not invite your two most bitter suppliers to the same meeting. You meet them separately. You whisper sweet nothings about volume to one while waving a competitor’s term sheet at the other. You make them fight. You extract every last drop of blood and margin. It’s Procurement 101.

Yet OpenAI did the unthinkable. It announced its strategic future with Samsung and SK Hynix not just in the same week, but in the same breath. This is almost unheard of in any industry, let alone one defined by such a fierce rivalry. It is like Ford and General Motors issuing a joint press release to announce they will both exclusively supply engines to a new global car brand. The act is so contrary to the established gospel of cutthroat competition that it begs the question: what kind of 4D chess is being played?

While the precise boardroom calculus will likely remain a secret, one can speculate. Perhaps it was the ultimate power move, a flex so profound it doesn’t just secure supply but reorganizes an entire industry’s dynamics for its own convenience. More likely, it was a move born of sheer, brutal necessity. The scale of demand for the Stargate project is so colossal, targeting up to 900,000 wafers per month, that it makes a mockery of playing suppliers off each other. By locking both rivals into the same grand project, OpenAI has effectively neutralized their ancient blood feud. Their focus can no longer be on stealing market share; it must be on the shared, all-consuming challenge of simply feeding the beast. The "War of the Roses" has been rendered obsolete by the arrival of an alien invasion.

If It’s So Easy, Why Not DIY?

The plot, as they say, thickens. We live in an era where OpenAI is not just a consumer of technology but a creator. It is reportedly developing its own bespoke AI chips, its own ASICs, in a clear and audacious bid to reduce its long-term reliance on NVIDIA. It is, in essence, looking at the most dominant and profitable chip company in history and saying, "We think we can do some of that ourselves."

And yet, where is the ambition to make its own HBM?

This question isn't just about technical hubris; it's a staggering political blind spot. Imagine the alternative universe: "OpenAI Announces Plan for Nation's First HBM Megafab in Ohio." The President would be at the groundbreaking ceremony, shovel in hand. It would be a masterclass in industrial patriotism, a resounding declaration that America's AI future will be built not just on American software, but on American memory. Instead, a deal potentially worth over $100 billion is flowing almost entirely overseas, a torrent of capital irrigating foundries in South Korea, a staunch ally, to be sure, but conspicuously not the American heartland.

And here is where the mystery truly deepens, expanding beyond a single company's strategy. We are witnessing a holy crusade among the tech titans, from Google and Amazon to Meta and Microsoft and every other one, all spending tens of billions to forge their own custom ASICs in a desperate quest to reduce their reliance on NVIDIA. There is a collective willingness to spend hundreds of billions reinventing every other part of the silicon stack. from custom training chips to complex server architecture.

Yet, in a stunning display of collective amnesia, none have announced a serious foray into making their own memory solutions. It is a strategic blind spot so glaring it must be deliberate. One is forced to conclude that manufacturing HBM is so mind-bendingly, capital-devouringly, soul-crushingly difficult that these giants have collectively looked at the challenge, gulped, and decided to just keep wiring money to Seoul.

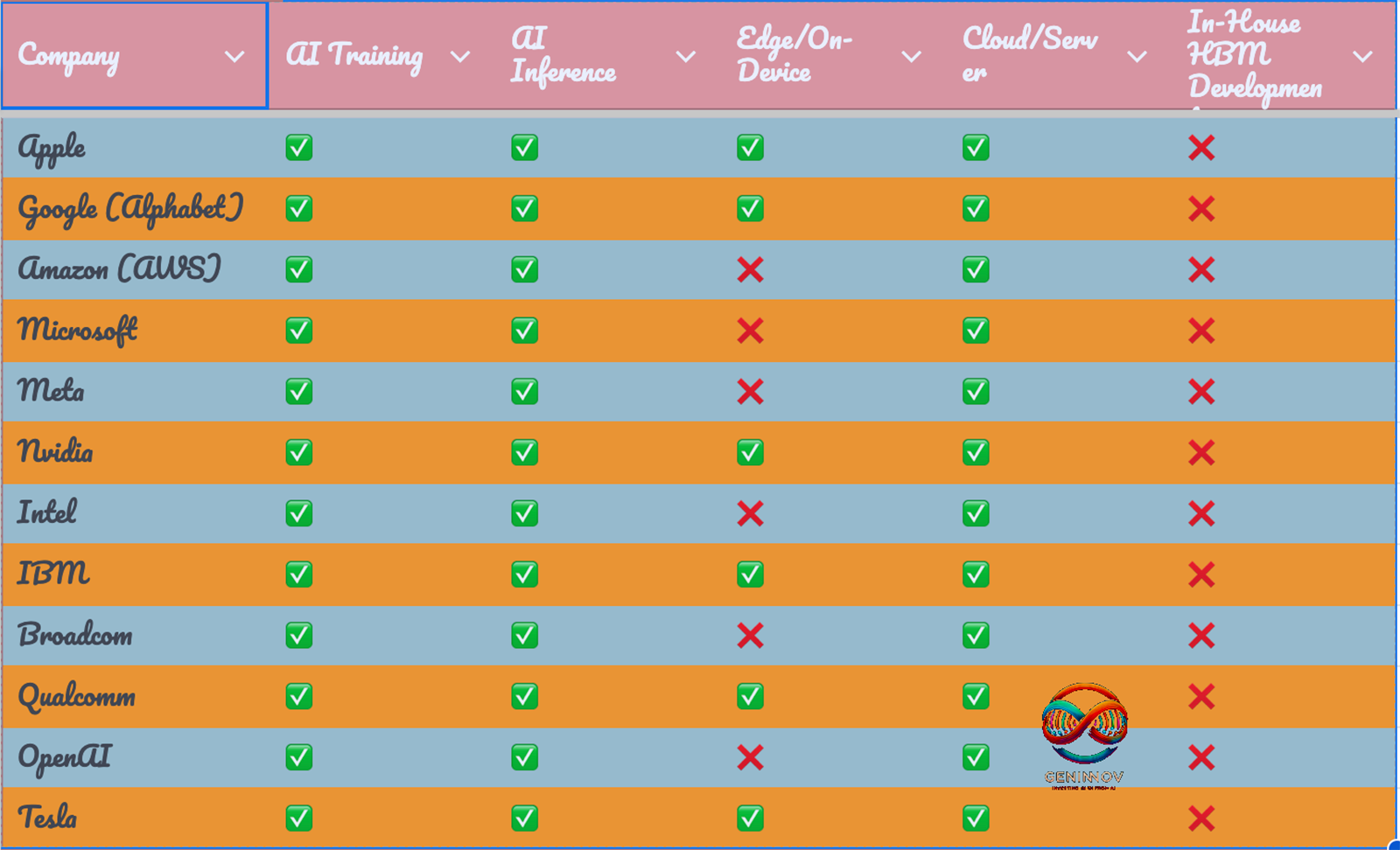

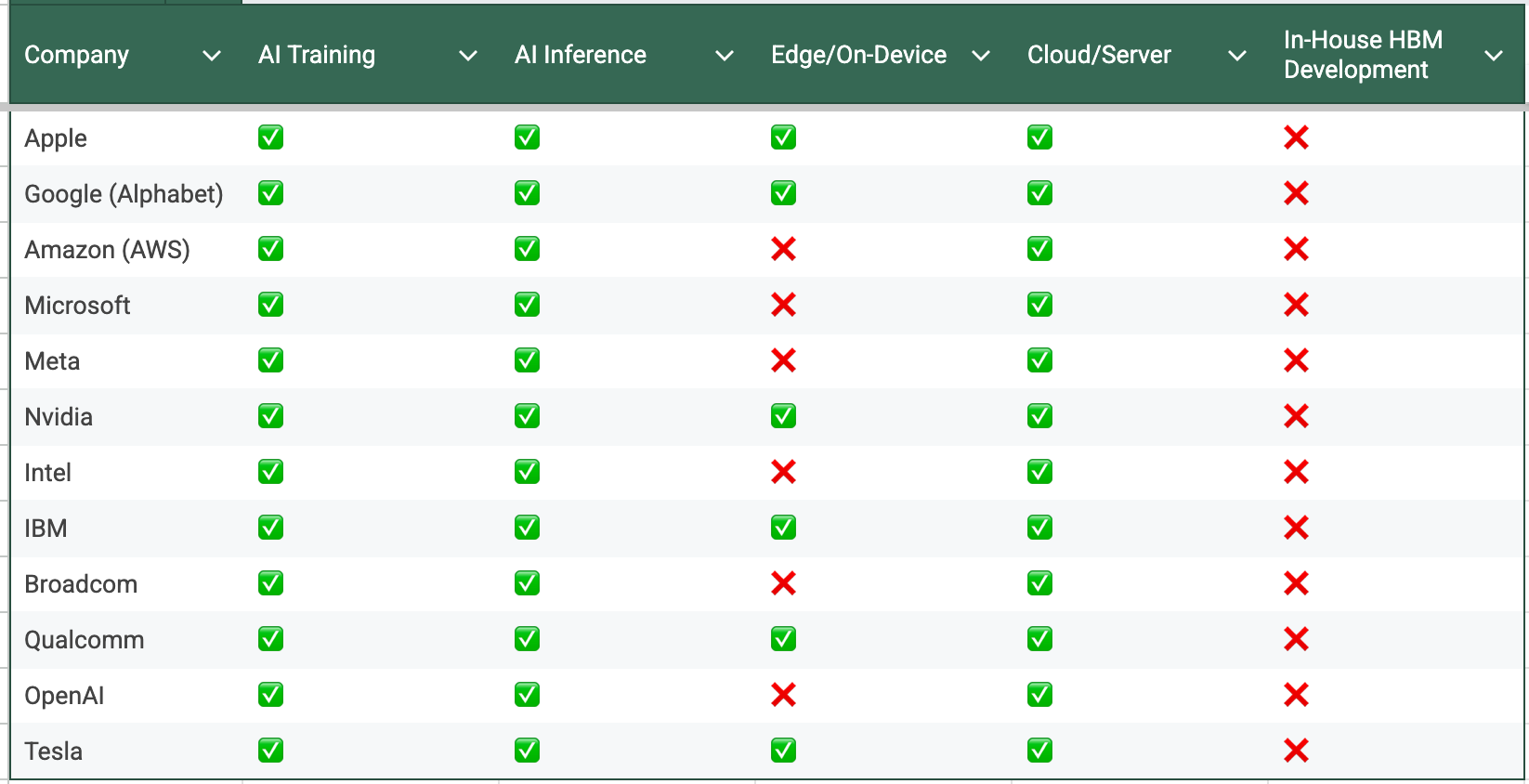

Giants ok to attempt all else in AI-silicon, except HBM

Not Your Grandpa’s Multi-Year Contract

It’s worth remembering that we have seen long-term memory contracts before. The most famous precedent is Apple's five-year deal in 2005 to secure NAND flash for the iPod. But that was a different world, and a different kind of deal. Back then, it was a buyer's market. Apple used its clout and a massive prepayment to secure a significant portion of the world's supply at what were likely very favorable and fixed prices. It was a move designed to protect Apple from supply shortages while simultaneously leveraging the fierce competition among suppliers to keep costs low.

The OpenAI LOI feels like the polar opposite. This is a seller's market. HBM is a scarce, high-value resource, and the power dynamic has flipped. OpenAI is not leveraging competition to drive down prices; it is leveraging its long-term demand to secure access at any reasonable price. The memory makers are not being squeezed; they are being courted. They have been given the kind of long-term participation promise, or volume commitment, that allows them to invest billions in new capacity as long as they have confidence in projects like Stargeate continuing.

And here is where the story gets truly interesting for the rest of the world. OpenAI is just one of a dozen-plus entities building massive AI infrastructure, as clear from the above table. In the boardrooms of other giants listed above, a cold sweat must be breaking out. The thought process is surely: "If OpenAI is locking down HBM capacity until 2029, what in the world should be our strategy?"

The scramble is on. The strategic importance of HBM capacity is beginning to resemble that of TSMC's 2-nanometer node. The irony is staggering. TSMC, for its monopolistic position in advanced manufacturing, is rewarded with a valuation that trades at a reasonable premium to the market. Its suppliers and partners are all anointed with the holy water of high multiples. Yet the makers of HBM are still discussed in hushed tones of "cyclical risk" and "Samsung fear".

Conclusion: The Gospel of Cyclicality Will Not Be Silenced

And yet, we know what will happen next, for the script of this tragicomedy is etched in stone. Even as a mountain of evidence transforms a mere "cycle" into a "super cycle," the market will refuse to see these technological marvels as anything more than glorified pork bellies. Every positive development for one company will be meticulously framed as a looming catastrophe for the other. The most optimistic price targets will still barely breach 15-20% above today's levels, and fund managers will continue to speak of these stocks in hushed tones, like a risky, slightly embarrassing secret hidden in the dark corners of their portfolios.

To be clear, in any short-term, the feuding giants are unlikely to shake off the disdain for each other, even if asked to work cooperatively by a client (which has happened) or provide better vibes by the President over a hypothetical dinner to life the market to the targetted “5000” level to lower the cost of risk capital (this event may remain in our dreams!). As habitual as their overt and covert undermining of each other will be the commentators’ obsession with daily developments rather than massive long-term implications.

The final absurdity is found only in the Korean market itself. It is a place so deeply possessed by the ghosts of the past that an earth-shattering, completely unexpected potential $100 billion deal can land with the force of a pebble in a pond, met not with a tidal wave of re-ratings, but with a shrug and a single-digit stock price move.