It’s not the crickets on social media that disappoint us. It’s the rather-too-often, earnest confession from unforgiving readers: “I read your piece three times, got ChatGPT too summarise, and I’m still not sure I get it.” We strive for clarity, for simplicity. Perhaps the problem isn’t our prose, but the very nature of the world we now inhabit. We are living through The Great Unsimplification, and nowhere is this more painfully obvious than in the world of innovation investing.

There was a time, not so long ago, when the investing world lived by the mantra of "Keep It Simple, Stupid" (KISS). When a visionary with a napkin could sketch the future Facebook or a nascent PageRank to the hurried, approving nods of a venture investor simultaneously tapping on the Blackberry. This was the golden age of the elevator pitch. The concepts were intuitive. Connecting people? A better way to search the web? A platform to rent a stranger's spare room? These were ideas grounded in relatable human experience. An investor could grasp the vision, feel the ambition, and make a decision based on a powerful, digestible narrative. The idea was the moat.

Many still cling to this romantic vision. We see it today in the excitement around "agentic AI." A founder sits across the table, painting a picture of an intelligent agent that will book our travel, fill out our tedious forms, and research topics on our behalf. We are intuitively drawn to this. It feels like the old magic. It feels simple. Contrast this in trying to guess the likely success of Cerebras Systems’ 4-trillion transistors in a single chip or Lightmatter’s 3-D stacked photonic superchip!

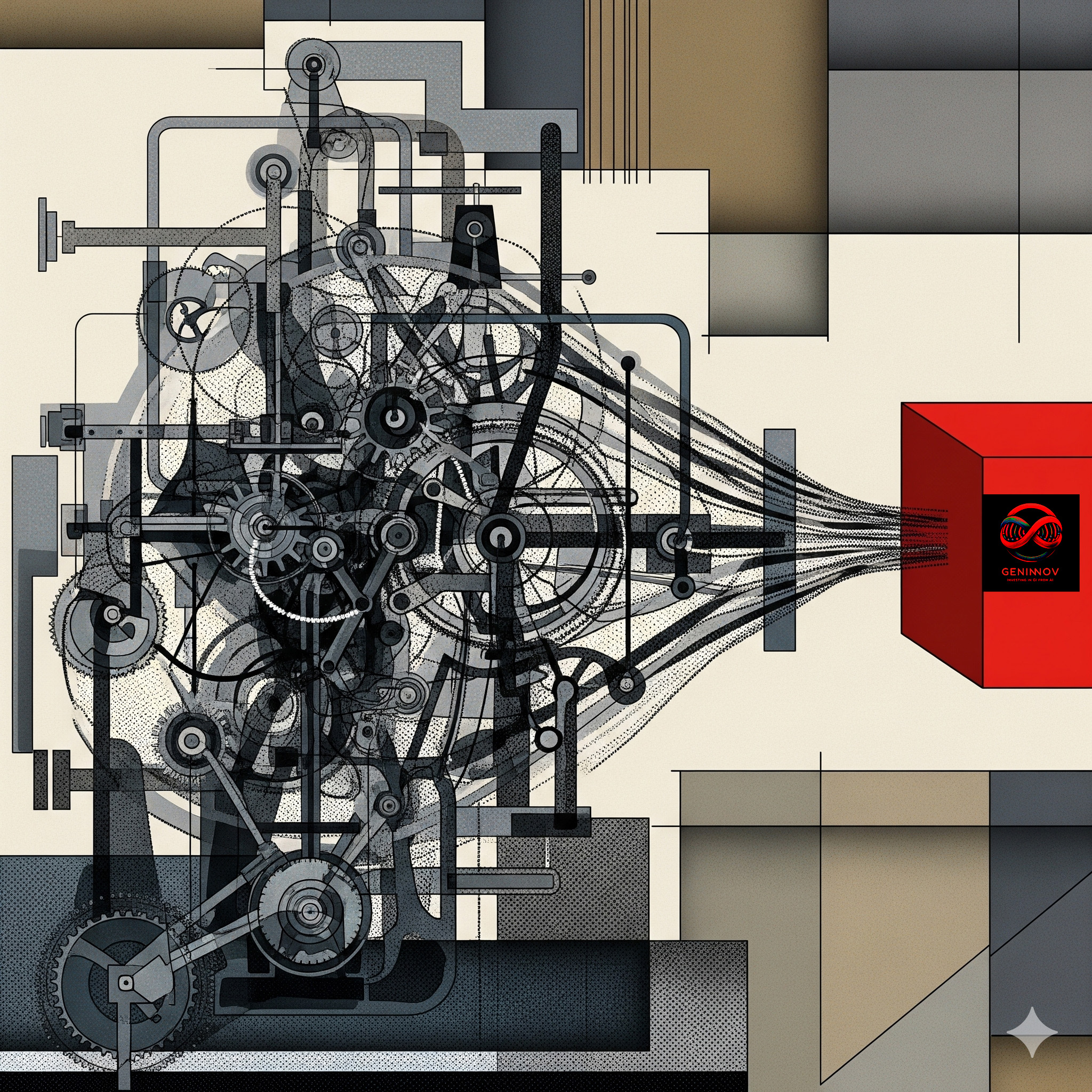

That world, the world where a simple, powerful idea was enough, is gone. The frontier of innovation has shifted from the relatable application layer to the bewilderingly complex hardware and deep-tech substrate. Investing today is no longer about backing a simple story; it's about navigating a labyrinth of acronyms, trade-offs, and brutal, evidence-based realities. And everyone, from the retail investor to the seasoned venture capitalist, is struggling to find their footing.

The Siren Song of Simple Stories: Turning Quantum into Quanta

"Never invest in a business you cannot understand." This pearl of wisdom, most famously attributed to Warren Buffett, has become a sacred text for investors. It’s a sensible rule born of a simpler time. The desire to adhere to this principle, to invest only in the comprehensible, has created a dangerous side effect: the forced translation of profoundly complex innovations into overly simple, often misleading narratives.

In today's innovation arena, the desire for simplification tempts us to shoehorn the incomprehensible into familiar tales. We crave emotive narratives, so we transform thorny tech into digestible proxies. A notable example is how AI hardware advances are often turned into stories of skyrocketing power demand.

It’s a beautifully simple tale. AI data centres are giant brains, and brains need energy. Therefore, investing in power generation is a direct, can’t-lose bet on AI. This narrative skillfully converts the intimidating complexity of silicon photonics, advanced semiconductor packaging, and esoteric memory architectures into a story about electricity, something everyone understands.

The narrative has genuine power, but it often dances on the edge of fiction. Proponents will tell you that a single AI query consumes as much energy as boiling a kettle, creating an emotive, visceral image. They will point to localized power shortages in data centre hubs and extrapolate a global crisis. The reality, however, is far more mundane. Most sober analysis suggests that without generative AI, global power demand was set to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 2.3% to 2.5%. With the AI boom, that figure might rise to between 3.0% and 3.5%. This is an acceleration with profound implications in many walks of life, including in the stability of the grid or the climate impact, to be sure, but it is hardly the revolutionary, grid-breaking explosion the storytellers would have you believe in the investment arena. It’s a laughably small increase in a mature, slow-moving industry.

The same dynamic plays out with nuclear energy. You will hear that data centres will fuel a nuclear renaissance, with growth projections hitting 12-15% annually. What the narrative conveniently omits is that nuclear power was already projected to grow at over 10% per year, driven by a global shift in the energy mix away from fossil fuels. The AI boost is marginal, not foundational, for the earnings prospects of any meaningful player in the industry. Yet, the simple story prevails because it offers a comforting, accessible proxy for an innovation—the AI hardware stack—that is fundamentally incomprehensible to most.

Writing about nuclear power is far easier than a rousing piece on NVLink72!

When 'New to Me' Masquerades as 'New to the World': The FP8 Feast

Every now and then, a piece of technical jargon escapes the confines of engineering labs and erupts into the financial consciousness, taking on a life of its own. It becomes a narrative anchor, a shorthand for a complex trend.

This week’s exhibit: FP8.

With the release of DeepSeek V3.1, FP8 — eight-bit floating point — became the darling of financial commentary. Investors who couldn’t tell FP8 from FP32 yesterday were now busy declaring it the future of AI efficiency.

The narrative power is undeniable. FP8 is easy to say, feels intuitive, and connects with popular themes: China’s push for local semiconductor self-reliance, DeepSeek’s engineering flair, and the eternal trade-off between precision and efficiency. A sentence like “FP8 halves the computational load without losing much accuracy” sounds simple, revolutionary, and investable.

The reality? FP8 isn’t new. Nvidia, Intel, and Google have been working with reduced precision formats for years. The choice of FP8 isn’t a universal truth but an engineering trade-off. Why not FP4 or FP64 (we are being facetious)? The answers are messy, context-dependent, and decidedly un-narratable.

FP8 is a genuine engineering step, but the hype is narrative-driven. Like many “new” concepts, it matters less for its technical revolution and more for its meme value. It allows a commentator to explain a seemingly new concept that feels graspable, lending them an air of technical authority. Some of these captured concepts have genuine power, but many, like FP8, are more notable for their narrative convenience than for being the revolutionary paradigm shifts they are made out to be. This is a hallmark of an era where understanding the story has become a substitute for understanding the science.

There Will Be Acronyms: The Case for Evidence-Based Investing

So, if simple narratives are a trap, what is the alternative? The answer is uncomfortable but unavoidable: we must wade into the complexity. There is no longer a shortcut. For those serious about investing in the foundational technologies of tomorrow, there is no choice but to engage with the bewildering world of details.

Take the battle for dominance in data centre interconnects—the technology that allows thousands of GPUs to talk to each other. You have Nvidia’s proprietary NVLink and InfiniBand competing against open standards like Ethernet and PCIe. Reading the marketing materials from any camp would convince you that their solution is the undisputed future and all others are doomed to obsolescence. This author, in a past life as a hardware seller, learned a harsh lesson: you can never, ever pick a winner by reading the spec sheet. The promises, the acronyms, and the theoretical benchmarks are a fog of war. Commercial success is an entirely different beast, determined by ecosystem, cost, reliability, and a dozen other factors that only reveal themselves in the real world.

The only way to navigate this is through a disciplined, patient, evidence-based approach. We must wait for the proof. Look at the high-bandwidth memory (HBM) market. SK Hynix established a clear lead in the HBM3 and HBM3e generations, becoming the preferred supplier for Nvidia's cutting-edge chips. Samsung, the perennial memory giant, was caught flat-footed. Now, as the industry looks towards HBM4, the narrative is shifting. Samsung is making bold claims, and it is entirely possible that they could leapfrog the competition and become the new leader. But how can an investor know? By reading press releases? By analyzing corporate statements? No. The only way is to wait for the evidence: the teardowns of next-generation accelerators, the supply chain contracts, the performance benchmarks from independent parties.

This principle extends to the furthest frontiers of science. We, like many, are deeply skeptical about the near-term commercial viability of quantum computing. This isn’t because the hardware progress isn’t remarkable—it is. It’s because there is a profound lack of evidence that quantum algorithms can solve any commercially relevant problem faster or cheaper than a classical supercomputer in the foreseeable future. Without that evidence, it remains a brilliant scientific pursuit, not a viable investment thesis. In a world of overwhelming complexity and competing claims, evidence is the only true north. The challenge is that by the time the evidence is clear, it might be too late. The art is to be waiting in the wings, prepared, so that when a winner does emerge, you are ready.

From Evidence to Endurance: Will Success Stick?

The crucial silver lining to this new age of complexity is that where moats do form, they are deeper and more defensible than ever. But they are forming in different places. The durable, winner-take-all dynamics that once defined application-layer companies like Google and Facebook have migrated down into the hardware stack.

If a company—be it Samsung or SK Hynix—truly cracks the code for the most efficient, highest-performing HBM4, that leadership could last for years. The capital expenditure, specialized knowledge, and manufacturing precision required create a formidable barrier to entry. The same is true for advanced packaging (CoWoS), interconnects, or next-generation lithography. A winner in these domains doesn’t just enjoy a fleeting advantage; they build a fortress. Their success creates a powerful flywheel of reinvestment and accumulated expertise, making it incredibly difficult for competitors to catch up.

Contrast this with the application layer. The world is abuzz with new AI methods and architectures. Last year, it was "reasoning models." This week, you might hear about "mixture of recursions" or "chains of layers." A new term gaining traction is AGS, or "Artificial General Scientist," as a more grounded alternative to AGI. These are fascinating concepts, and they produce incredible demos. A model that uses one of these techniques might top the leaderboards for a few weeks. But then what? The ideas are published, the methods are reverse-engineered, and within months, every major competitor has incorporated a similar approach, if it is a genuinely great approach.

The very agentic AI systems that sound so appealing suffer from this same vulnerability. An agent that can flawlessly book a flight is a marvel of utility, but it has no business moat in a world of instant copyability. There is no platform effect, no network effect, no sticky ecosystem. The hard-won advantage of a software breakthrough can evaporate overnight.

There are far more great ideas these days compared to ever before that result in great products and services, but not great businesses.

The Great Unsimplification

This shift towards deep, biotech-like complexity is not confined to semiconductors. Look at robotics. The conversation is no longer just about which company has the most human-like robot. It's about the brutal economics of actuators, the trade-offs in various sensor modalities, and how to navigate a market where proposed solutions range from a $300 specialized device to an $80,000 humanoid. To form a coherent investment view requires embracing this messy, multi-variable reality.

Or consider biotechnology itself, the original home of inscrutable innovation. One might hear about a company like WuXi AppTec and its state-of-the-art platform for Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD). Will this technology result in a dozen blockbuster drugs and a massive business? No senior executive, no matter how eloquent, can give you a human-language explanation that can definitively answer that question. The path from a promising scientific platform to a successful drug is a graveyard of plausible theories. Investing in the picks and shovels of this world—the makers of novel antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) or new protein sequencing methods—is fraught with the same challenge. Understanding the narrative is not enough.

For decades, consumer internet and software were the great exceptions. They were a wonderful anomaly where human intuition could grasp the core of an innovation and its business potential. That era is over. The rest of technology is now reverting to the mean, becoming more like biotech and advanced manufacturing, where progress is opaque, non-intuitive, and brutally difficult to forecast.

Escaping this complexity is no longer an option for the serious innovation investor. We have two choices. The first is to commit to the grind ourselves: to learn, to read the papers, to talk to the engineers, and to slowly, painstakingly build a framework for understanding that is grounded in evidence, not narrative. The second is to entrust the task to those who have made navigating this labyrinth their sole focus.

Either way, the message is clear. The simple world is behind us. The age of the elevator pitch is over. Welcome to The Great Unsimplification.