The Indifference Paradox: Where Material Announcements Meet Market Shrugs

At GenInnov, we are often told that we write a lot. And we do. We have our reasons, which we have explored previously. In some ways, Innovent Biologics reminds us of ourselves. The company issues press releases at a relentless pace, each announcing partnerships, clinical milestones, or regulatory breakthroughs that would be considered transformative for any pharmaceutical company worldwide. What we have observed, however, is that the market has turned almost completely indifferent to these announcements. Deals worth billions of dollars, trial results that place Innovent among the most innovative drug developers globally, and regulatory designations from the FDA itself produce little more than a brief flicker on the stock chart before the price settles back to where it started.

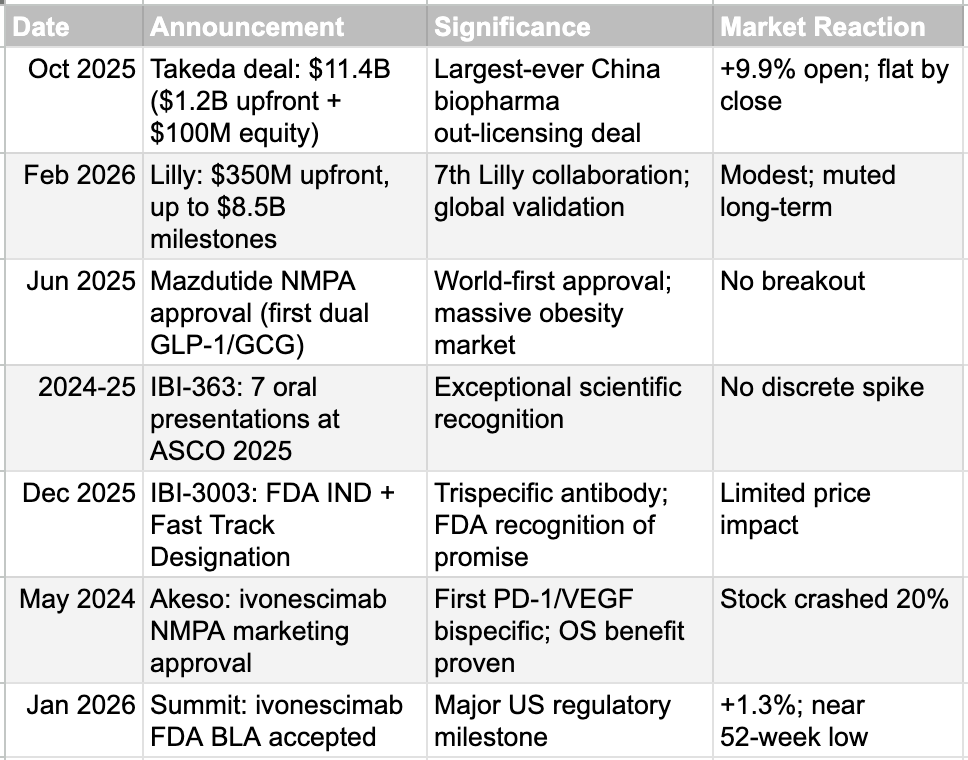

Consider the evidence. In October 2025, Innovent announced an $11.4 billion deal with Takeda, including $1.2 billion upfront and a $100 million equity investment. The stock spiked 9.9% at the open and finished the session down 1.2%. Over the weekend, Eli Lilly committed $350 million upfront, with milestones totaling $8.5 billion for its seventh collaboration with Innovent. The reaction was modest by the standards of what something similar might have caused for a company listed in the West. Mazdutide, the world's first dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonist, received NMPA marketing approval without so much as a breakout on the chart. IBI-363 earned seven oral presentations at ASCO 2025. IBI-3003 received both FDA IND approval and Fast Track Designation. None of these produced a discrete, sustained price move. Similar announcements from a Western pharmaceutical company would very likely have driven significant and lasting stock appreciation.

This indifference is not limited to Innovent. Akeso's stock crashed 20% when the NMPA approved ivonescimab, a potentially best-in-class PD-1/VEGF bispecific antibody that demonstrated both progression-free and overall survival benefits. Summit Therapeutics, Akeso's US partner, saw its stock move just 1.3% when the FDA accepted the BLA filing for ivonescimab in January 2026. The stock now trades near its 52-week low. One can ascribe some of this indifference to the nature of the Hong Kong and China investor base, to the mechanics of Volume-Based Procurement that compress domestic margins, or to the general risk-off sentiment surrounding Chinese equities. But beneath all these factors lies a more fundamental and persistent question: can any clinical trial data from China be trusted? We believe this question deserves a serious, evidence-based examination.

The History Paradox: Distrust That Was Earned

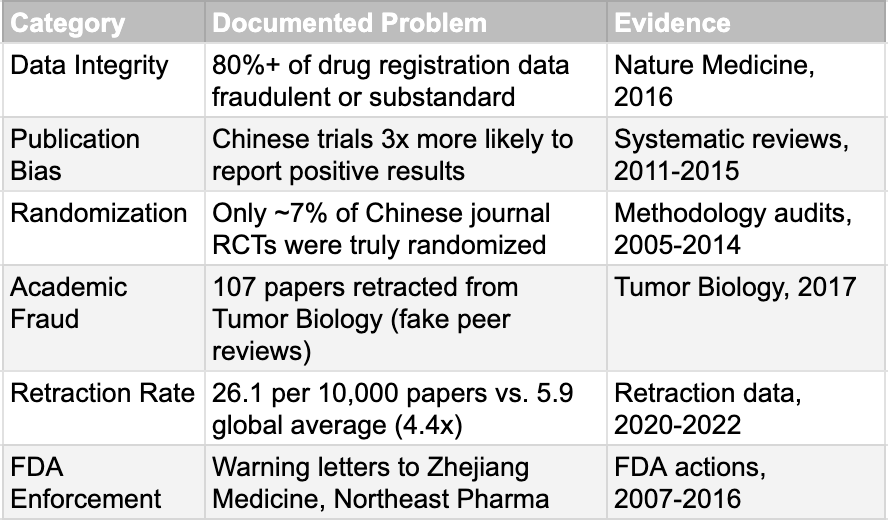

We must concede that the skepticism is not without origin. There is a specific historical trauma that helps explain global investors' wariness, and it centers on July 22, 2015. On this date, the Chinese regulator (then the CFDA) launched a "self-examination" campaign that led to a catastrophic exposure of systemic failure (see the next section for details). The numbers from that period are damning. When forced to verify their own data under threat of penalty, sponsors voluntarily withdrew more than 80% of pending drug applications. A 2016 report published in Nature Medicine asserted that just over 80% of clinical trial data submitted to support new drug registrations in China had been revealed as fraudulent or substandard. While that exact figure has been debated, the underlying reality was undeniable. The process of conducting clinical trials in China was significantly less standardized and less transparent than in Western countries. Publication bias was rampant, with Chinese trials approximately three times more likely to report positive results than non-China trials. Only about 7% of randomized controlled trials published in Chinese journals between 2005 and 2014 were determined to have been truly randomized. The FDA issued warning letters to companies including Zhejiang Medicine and Northeast Pharmaceutical Group for data integrity violations. These were not isolated incidents but symptoms of a system where data quality was not the primary concern.

This matters because narratives formed during crises tend to linger long after conditions change. In financial markets, memory is sticky. Reputational damage compounds. Even when reforms are enacted, belief updates slowly, if at all. The history paradox lies in the fact that skepticism today is often rooted in a past that no longer exists.

The Reform Paradox: Change Without Belief

On July 22, 2015, China's CFDA launched what would become the most consequential self-examination in pharmaceutical regulatory history. The campaign covered 1,622 pending drug applications and required all sponsors to verify the authenticity and integrity of their clinical trial data. By June 2016, 1,193 of 1,429 self-examined applications, approximately 83%, had been voluntarily withdrawn. The CFDA blacklisted implicated CROs and trial investigators. China's Supreme Court issued a judicial interpretation making trial data fabrication a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment. This was not a cosmetic exercise. It was a deliberate demolition of the old system.

What followed was a comprehensive reconstruction. In June 2017, China became a full member of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), committing to align its regulatory standards with the highest global benchmarks. The CFDA was restructured into the NMPA, with substantially improved transparency, dramatically reduced approval timelines, and a new emphasis on evidence-based decision-making. China's revised GCP regulation, introduced in 2020, met the requirements of the ICH E6(R2) guideline and introduced risk-based monitoring. The NMPA has since released draft plans to implement ICH E6(R3), which emphasizes adaptive trial designs and sophisticated data analytics. Median NDA approval times fell to 15.4 months. Annual approvals reached 70 new drugs in 2021. Chinese participation in multiregional clinical trials grew from 5 trials in 2015 to 53 in 2022, and in 2024, China surpassed the United States for the first time in the number of new clinical trial starts.

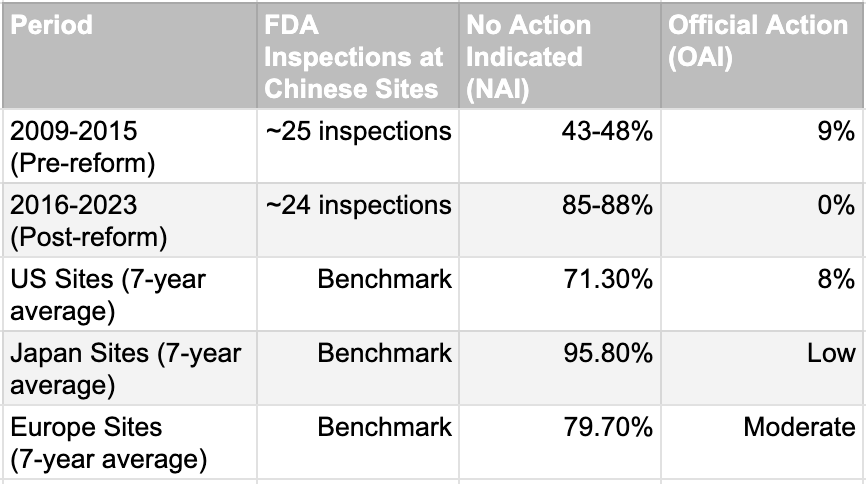

The improvement is extraordinary and measurable. Chinese trial sites went from worse than the US average to comparable or better in FDA inspection outcomes. The No Action Indicated rate rose from 43-48% to 85-88%, a 37-percentage-point improvement in seven years. Official Action Indicated findings, which represent the most serious quality failures, dropped from 9% to zero. Post-reform Chinese sites now perform better than the average US site and approach Japanese standards. This is one of the fastest quality transformations in global clinical trial history. The question is no longer whether China fixed the problem. It did. The question is whether the world has noticed.

The CRO Paradox: Trusted Infrastructure, Untrusted Innovators

There is a paradox at the heart of distrust of Chinese clinical trial data, and it deserves far more attention than it receives. The world's largest pharmaceutical companies routinely use Chinese contract research organizations and Chinese clinical trial sites to generate data for their own global drug submissions. Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca all conduct trials in China through CROs like WuXi AppTec, Tigermed, and Pharmaron. WuXi alone generated nearly $3 billion in revenue in 2023, making it Asia's largest CRO. The data from these trials passes FDA and EMA scrutiny without controversy. Yet when Chinese innovator companies run their own trials at the very same hospitals, using the very same investigators and laboratories, the resulting data is treated with suspicion. This cannot be explained by infrastructure quality, because the infrastructure is identical.

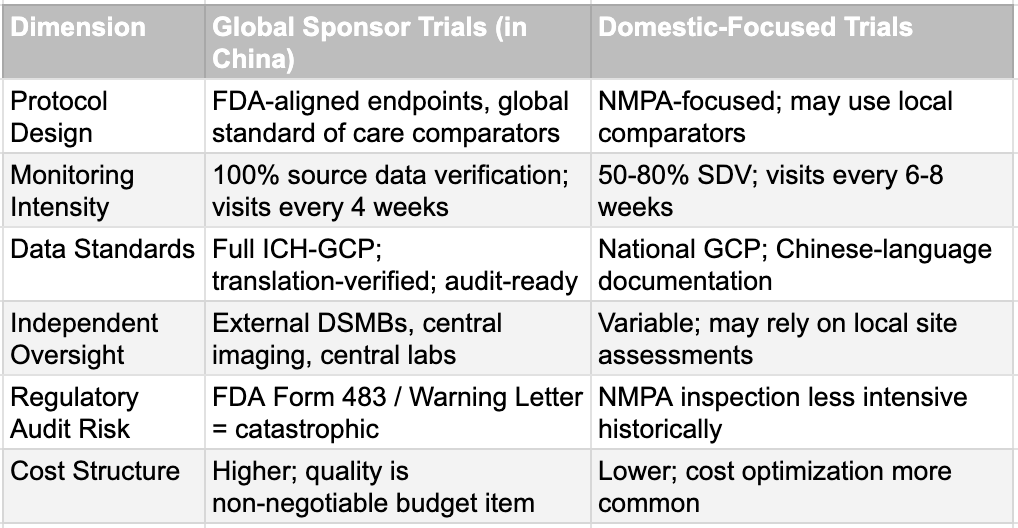

The explanation lies in the processes, not the places. When Pfizer engages a Chinese CRO for a Phase III trial destined for an FDA submission, it imposes its own standard operating procedures, requires 100% source data verification, deploys international monitors, and structures the documentation to withstand the most rigorous regulatory audit. The CRO knows that any deviation could result in losing a major client and attracting a public FDA scolding. The expectation of perfection is non-negotiable. In contrast, when a domestically focused Chinese biotech sponsors a trial intended solely for NMPA approval, the same CRO may operate with somewhat different parameters. Monitoring visits may occur every eight weeks instead of every four. Critical data verification may cover 50% rather than 100%. Documentation may remain in Chinese without translation-checking. These differences do not necessarily indicate fraud, but they represent a divergence in rigor that is driven by economic incentives and historical regulatory expectations.

This two-tier reality is important to understand because it indicates that not all Chinese clinical trial data are equival. Data generated under global oversight with FDA-grade monitoring and internationally standardized processes should be evaluated on the same basis as data from any other country. Data from a purely domestic pipeline, particularly from the pre-reform era, legitimately warrants additional scrutiny. The CRO paradox, however, also reveals something uncomfortable about the nature of the skepticism. If the concern were genuinely about the quality of Chinese sites, it would apply equally to Pfizer's and Innovent's Chinese trials. It does not. The differential treatment points to the question of whether any Chinese drug makers are applying the standards enforced by global giants. If they do, the processes or the abilities will not be a hindrance.

The Ambition Paradox: Same Country, Different Standards

The strategic orientation of a Chinese biopharmaceutical company is arguably the most important determinant of the quality and global acceptability of its clinical trial data. Companies that aspire to global markets do not design trials the same way as those targeting only the Chinese domestic market. The difference is visible from the very first protocol. Globally ambitious companies design large, randomized, multicenter, controlled trials that include patients across multiple geographies and ethnic backgrounds. They engage with the FDA early, often through pre-IND meetings, and they structure their endpoints, comparators, and statistical plans to meet the expectations of the world's most demanding regulatory agencies. This is not an incremental difference. It is a fundamentally different approach to drug development.

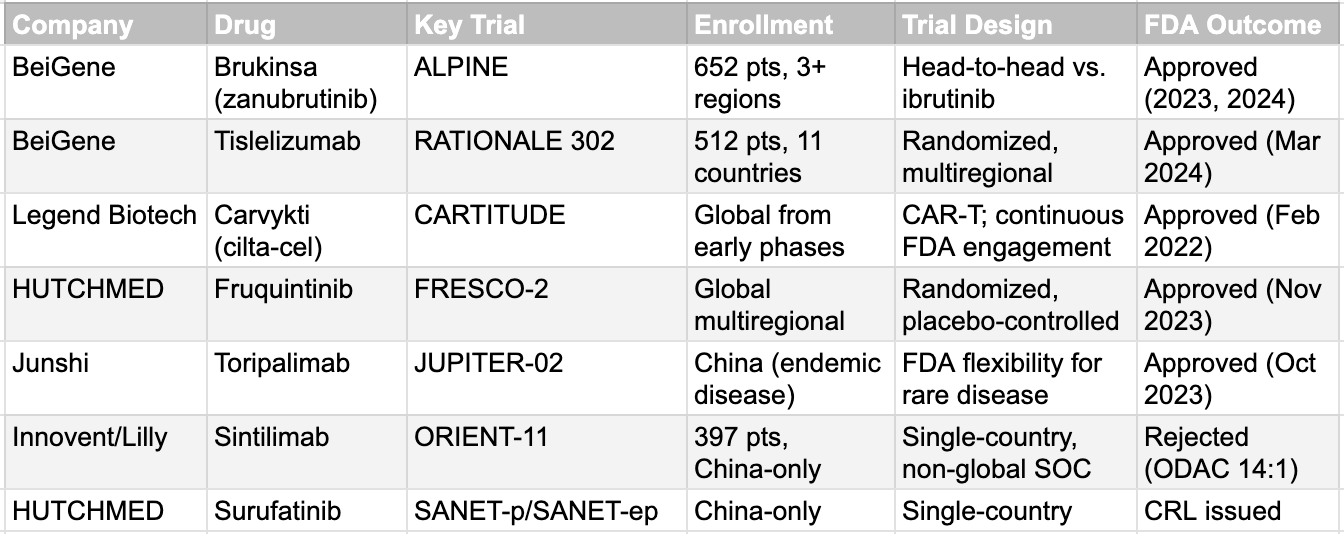

BeiGene is the clearest illustration. The ALPINE trial for zanubrutinib enrolled 652 patients across North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and China. It was a head-to-head comparison against ibrutinib, the global standard of care, with a primary endpoint of superior progression-free survival. The data was analyzed by region to ensure consistency. The result: FDA approval in 2023, with Brukinsa now approved in over 70 markets. The RATIONALE 302 trial for tislelizumab enrolled 512 patients from 132 sites across 11 countries. Again, global from inception. Again, FDA approved in March 2024. Legend Biotech's Carvykti, a BCMA-targeted CAR-T therapy, achieved FDA approval because the CARTITUDE program incorporated global sites from early phases and maintained continuous engagement with the FDA on manufacturing and chemistry. HUTCHMED's fruquintinib earned FDA approval in November 2023 through the FRESCO-2 global trial, supplementing earlier Chinese data with a robust international dataset.

The pattern is unmistakable. Every Chinese-originated drug that achieved FDA approval did so through multiregional trials designed from the start for global scrutiny. Every rejection involved China-only data. The lesson is not that Chinese data is inherently untrustworthy. The lesson is that trial design, strategic intent, and regulatory engagement determine outcomes. Companies like BeiGene, Innovent, and Hengrui now employ experienced regulatory consultants, often former FDA or EMA officials, to ensure their development programs meet every expectation. Hengrui became the world's top clinical trial sponsor in 2024, overtaking AstraZeneca. These are not companies working in isolation. They are operating at the frontier of global drug development.

The Double Standard Paradox: Geography Over Science

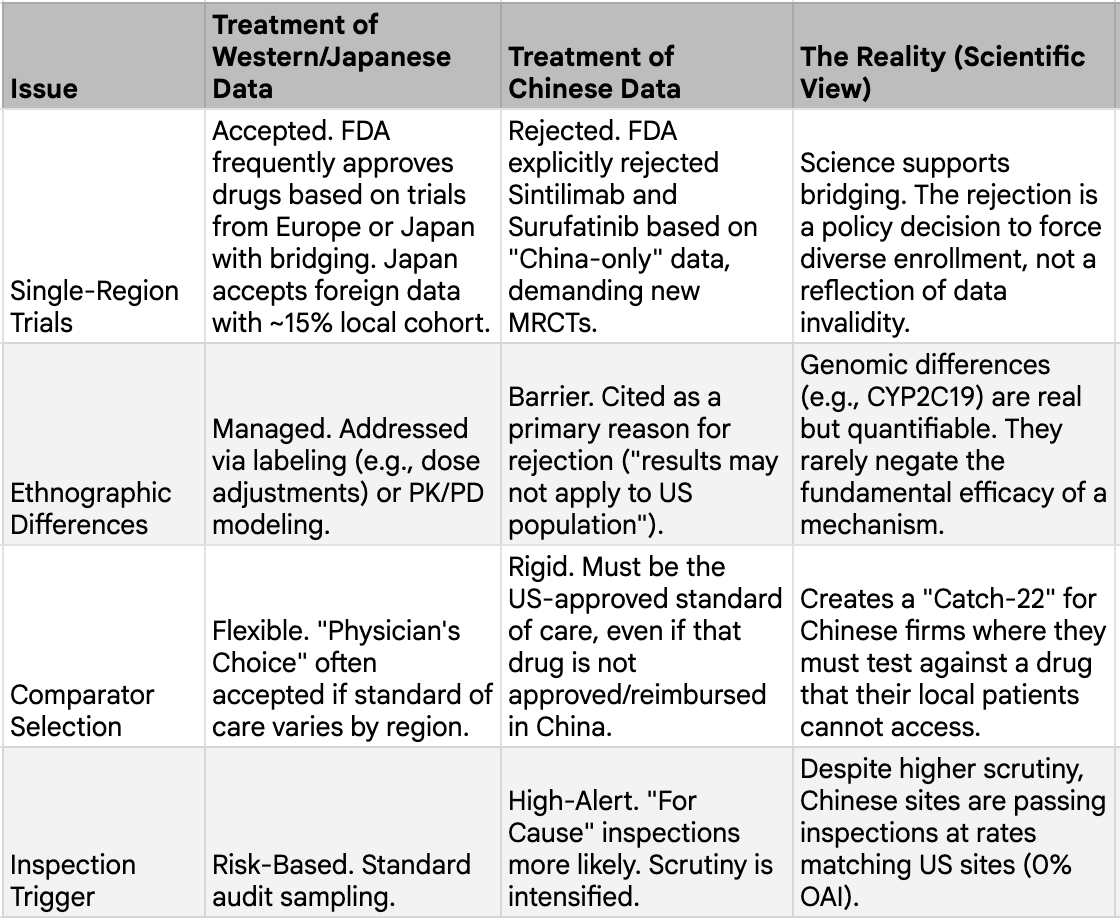

The FDA's treatment of Chinese clinical trial data is unambiguously stricter than its treatment of data from other single-country sources. The 14:1 ODAC vote against Innovent's sintilimab in February 2022, based on the China-only ORIENT-11 trial, established a precedent that single-country Chinese data would not be accepted for most indications. The rejection of HUTCHMED's surufatinib, despite two positive Phase III trials demonstrating 51% and 67% reductions in the risk of progression, reinforced this position. The sole exception has been toripalimab for nasopharyngeal carcinoma, a disease so rare in the United States that the FDA granted regulatory flexibility. But the toripalimab exception proves the rule: for any globally prevalent condition, China-only data are effectively rejected.

The stated concern is ethnic homogeneity. Chinese trials typically enroll populations that are more than 95% Han Chinese, and the FDA reasonably asks whether results from such populations can be extrapolated to the diverse American patient base. There are genuine pharmacogenomic differences that support this concern. CYP2C19 poor metabolizers represent approximately 19% of the East Asian population versus just 2% of Caucasians, a tenfold difference that meaningfully affects the metabolism of drugs including clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. HLA-B*15:02, which is associated with severe carbamazepine reactions, is far more prevalent in Han Chinese populations. Beyond genetics, Chinese cancer patients present at later stages (72.4% of breast cancer patients at Stage II-IV versus 48.8% in the US), have different biomarker profiles, and carry different comorbidity burdens. These are legitimate scientific considerations.

However, there is a symmetry problem that is rarely discussed. Japanese Phase III trials have historically enrolled populations that are more than 95% Japanese, yet Japan-only data has been integrated into global regulatory frameworks with far less friction. US clinical trials were more than 90% white through the 2000s. A 2001 Surgeon General's report found that out of 10,000 randomized trial participants for psychiatric and neurological conditions since 1986, only 561 were African American, 99 were Latino, 11 were Asian American, and zero were American Indian. If ethnic homogeneity were the primary basis for rejecting clinical data, the standard should apply equally to all countries. It does not. Western companies have conducted pivotal trials largely in Eastern Europe, India, or Latin America with few or no US patients, and those drugs were approved by the FDA without comparable controversy. Pharmacogenomic differences that affect Chinese populations also affect Japanese and Korean populations equally, as they are East Asian characteristics rather than uniquely Chinese ones. Yet only Chinese data are subject to this degree of regulatory skepticism.

The ICH E5(R1) framework provides the scientific answer. It states that foreign clinical data can be accepted without duplicative local trials if the influence of ethnic factors is adequately evaluated. The guidance does not require identical efficacy across populations. It requires assessing whether observed differences are clinically meaningful and whether dosing adjustments are warranted. For the majority of modern drugs, particularly in oncology and metabolic disease, the scientific consensus is that drug effects are more influenced by intrinsic drug properties and disease biology than by ethnicity. Population pharmacokinetic analyses for drugs like tepotinib, a MET inhibitor, have shown no relevant race effects, with consistent exposure-response relationships across Asian and non-Asian populations. The same dataset was accepted by the FDA, Japan's PMDA, and China's NMPA. With sufficient quantitative evidence, the totality-of-evidence approach can make dedicated bridging studies unnecessary.

The companies with global ambitions understand this. They design their early Chinese trials with future extrapolation in mind, collecting pharmacokinetic data across subgroups, running population PK modeling, and building the evidence base that will support global submissions. Innovent's newer programs, developed after the sintilimab experience, are global from the start. BeiGene's ALPINE trial was specifically designed to slice data by region and demonstrate consistency. The issue is not that Chinese data cannot support global approval. It is that it must be generated with that intent from the beginning.

The Evidence Paradox: Signals Without Prices

We conclude with a Bayesian perspective. The weight of evidence has shifted decisively, but the market's priors have not updated. A long list of Chinese companies is producing phenomenal trial results that are being systematically underpriced. When the market sees Akeso's ivonescimab beat Keytruda and the stock falls, it is pricing in a 2015-era probability of failure. It assumes the data is flawed, the regulator is hostile, or the commercial opportunity will be regulated away.

But consider the actions of the entities that actually diligence the data. Eli Lilly did not commit $8.5 billion in milestone payments to Innovent without scrutinizing the raw trial data. Takeda did not structure an $11.4 billion deal without forensic verification. GSK did not arrange a $12 billion partnership with Hengrui on faith. These are the most sophisticated pharmaceutical companies in the world, and they are voting with their balance sheets. They are validating the science that the stock market ignores.

The successes are compounding. Legend's Carvykti is a commercial blockbuster. BeiGene's Brukinsa is taking global market share across 70 countries. Fruquintinib, tislelizumab, and toripalimab have all cleared the FDA. These are not one-off anomalies. They are the new baseline. Yes, companies will need additional time and funding to conduct multiregional trials and bridging studies required by the FDA and EMA. That introduces cost and delay. But the early clinical successes observed in China are highly unlikely to be reversed when tested in broader populations. Pharmacology does not change with geography. Disease biology does not change with ethnicity for the vast majority of these drug targets. The accumulated weight of evidence across multiple drugs and multiple companies over five years strongly supports a single conclusion: well-designed Chinese trials produce reliable data.

This is the final paradox. The science is becoming impossible to ignore, yet prices still behave as if nothing has changed. We are not betting on blind trust. We are betting on the widening asymmetry between a scientific reality that has already moved and a market perception that has not. That gap is where opportunity lives.

It is perhaps fitting that we are writing this as we transition from the Year of the Snake to the Year of the Horse. We leave behind a symbol often associated with the serpent paradox—simultaneously representing hidden danger and the power of healing—much like the dual nature of the data we have discussed. We now enter the Year of the Horse, a symbol of speed, endurance, and unbridled forward momentum. The industry has shed its old skin. It is time for the market to catch up to the gallop. We wish you a very Happy Lunar New Year.