A few weeks ago, Akeso reported that ivonescimab had become the first immunotherapy ever to extend survival in EGFR-mutated lung cancer patients who had failed prior treatments. This is a patient population in which Merck's Keytruda, the world's best-selling cancer drug with $25 billion in annual sales, has never worked. In head-to-head trials, ivonescimab has now beaten Keytruda three times. The investment community shrugged.

Last month, Innovent unveiled Phase 1 data for IBI3003, a trispecific antibody for multiple myeloma. In patients who had failed a median of four prior treatments, the response rate was 83%. The standard-of-care response rate for these patients is 30%. The drug worked even in patients whose cancers had already escaped the targets that existing blockbuster therapies go after. Days ago, the FDA granted it Fast Track designation. Again, almost no one in markets or media seems to have noticed.

These "shocks" are no longer outliers; they are a new, regular phenomenon. After decades of being dismissed as a "copycat" factory, China has built an innovation engine that is now out-discovering the giants. To find the investment alpha hidden in this indifference, we have to look back at the cinematic, twenty-five-year climb. This is a story of "Sea Turtle" scientists, industrial bootcamp, and a quiet mastery that has turned the world's pharmacy into its premier laboratory.

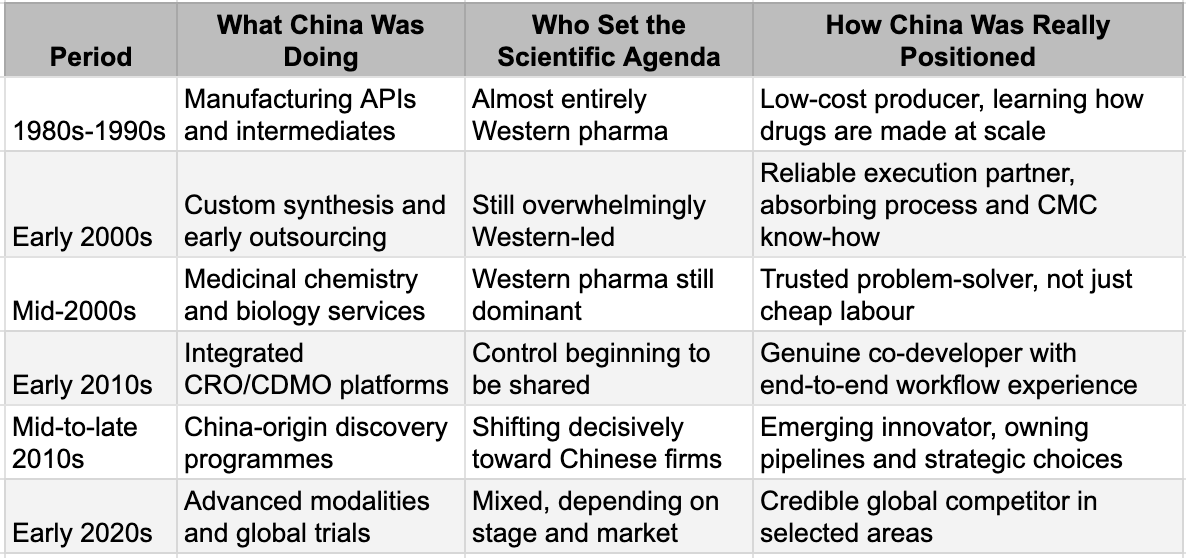

The Bootcamp (1980s-1999)

In Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee's character doesn't charge at his opponents. He enters the tournament, studies the rules, observes how power operates, and builds his advantage through discipline and repetition before anyone recognises the threat. TSMC followed the same script. Before it became the world's most valuable semiconductor company, it spent years making chips for other people's designs. The learning came not from inventing new architectures but from executing thousands of production runs under the most demanding quality standards in the industry. Process discipline, yield optimisation, defect analysis - the unglamorous work that separates theoretical capability from commercial reality.

China's pharmaceutical industry followed the same playbook.

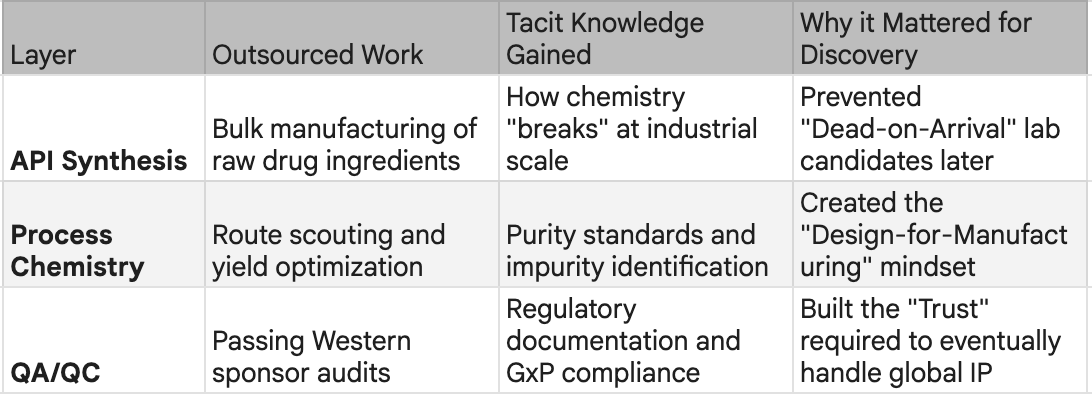

Through the 1980s and 1990s, as Western pharma moved up the value chain toward blockbuster biologics and targeted therapies, someone had to manufacture the commodity inputs: active pharmaceutical ingredients, chemical intermediates, the building blocks of global medicine. China took that work. It was low-margin, capital-intensive, and unglamorous. It was also an education.

Repetition across thousands of production runs built something that couldn't be bought or licensed: tacit knowledge of how drugs are actually made at scale. Synthesis, purification, quality control, yield optimisation - the industrial fundamentals that separate a promising molecule from a manufacturable medicine. By the late 1990s, China had deep operational fluency in pharmaceutical manufacturing. This was not innovation. But it was the foundation on which innovation would be built. In numbers, if Japan and the US had over 90% of global APIs in the mid 1990s, by mid 2010s, China was producing over 40% and ranked first in world output of penicillin, vitamins, antipyretics, and analgesics. However, what China learnt was more than the manufacturing of the molecules discovered by others. The path from that foundation to today's breakthroughs followed a specific sequence and explains why China succeeded where other low-cost manufacturing bases did not.

From Industrial Participation to Innovation Capability

Learning Matrix

The Dojo (2000-2010)

The boot camp produced workers. The next phase would produce masters.

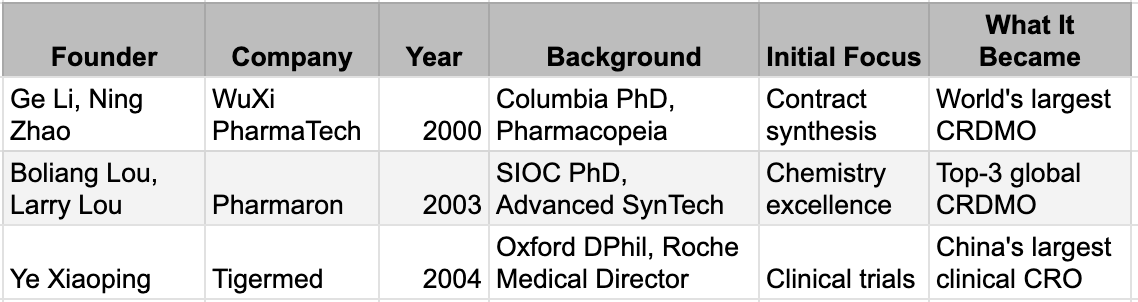

In 2000, a 33-year-old chemist named Ge Li returned to Shanghai. He had earned his PhD at Columbia, worked at Pharmacopeia in New Jersey, and understood something that would prove decisive: Western pharmaceutical companies didn't just need cheap labour. They needed partners who could solve problems, meet deadlines, and operate under the quality systems that regulators demanded. He founded WuXi PharmaTech with three co-founders and $2 million, starting in a 7,000-square-foot laboratory.

The model was deceptively simple. Multinational drug companies were under relentless pressure to cut R&D costs. Outsourcing chemistry work to China offered savings, but only if the work met Western standards. WuXi's edge was not price alone. It was that Ge Li and his team understood what "meeting Western standards" actually meant - the documentation, the quality systems, the communication rhythms, the unstated expectations. They had lived inside the system, they were now serving from outside.

The capability stack grew methodically. Custom synthesis in 2001. Process development in 2003. Bioanalytical services in 2005. Toxicology in 2007. Small-scale manufacturing in 2008. Biologics in 2011. Each addition was validated not by investors but by clients - Pfizer, Merck, Novartis - who returned with larger contracts because the work was good.

WuXi was not alone. In 2003, Boliang Lou and his brother Larry, both trained in the US, founded Pharmaron with a focus on the hardest chemistry problems sponsors could throw at them. In 2004, Ye Xiaoping, who had been a medical director at Roche, founded Tigermed to build a clinical trial infrastructure. Each company targeted a different slice of the drug development process. Together, they were assembling the complete stack.

What made this phase transformative was not the companies themselves but what happened inside them. Every contract was a lesson. A Western sponsor designing a kinase inhibitor would send the project to WuXi for synthesis. WuXi's chemists would see not just the target molecule but the design rationale, the SAR logic, the failure modes that had been tried and abandoned. Multiply this across hundreds of programmes from dozens of sponsors, and something unprecedented accumulated: a library of tacit knowledge about what works, what fails, and why.

This was the real technology transfer - not through formal licensing or joint ventures, but through the daily work of making molecules for the world's most sophisticated drug developers. The learning was not theoretical. It was earned through repetition, feedback, and the unforgiving discipline of client audits.

By 2010, WuXi employed over 10,000 people and had served thousands of clients. The platform had touched more drug programmes than any single pharmaceutical company's internal R&D organisation. The question was no longer whether Chinese scientists could execute Western designs. It was what would happen when they started designing for themselves.

The Breakout (2010-2018)

The transition from service to sovereignty happened faster than anyone predicted.

In late 2010, John Oyler and Xiaodong Wang founded BeiGene with a principle that would prove decisive: they would not build a company to be sold. Oyler had already built and sold BioDuro, a drug-discovery services firm, and understood the drawbacks of the contract research model that kept Chinese scientists in a permanent supporting role, executing others' ideas. Wang, a member of the US National Academy of Sciences and former Howard Hughes investigator, believed the talent now existed to do original work. What was missing was the organisation willing to attempt it. BeiGene was founded to become a global biopharmaceutical company with Chinese roots that was not a subsidiary, not a regional play, not a candidate for acquisition.

They were not alone. Michael Yu founded Innovent in 2011 after observing that over 90 percent of American patients who qualified for monoclonal antibody therapies had access to them; in China, the figure was 6 percent. Michelle Xia and her co-founders launched Akeso in 2012 with less than $3 million and no salaries, betting that world-class antibody research could be done at a fraction of Western costs. Samantha Du, who had already co-founded Hutchison MediPharma, was renowned for mentoring a generation of biotech entrepreneurs, started Zai Lab in 2014. Each company had a different initial strategy in discovery, biosimilars, or licensing, but the same endgame: building organisations that could eventually compete globally on their own terms.

What distinguished this generation was timing. The talent pipeline had reached critical mass through two decades of CRO work and the return of the sea turtle generation. The sum total meant that BeiGene could recruit more than 100 scientists in its first months simply by announcing it was open for business. The capital markets and regulators provided their impetus, although they could not have caused the innovation factories to begin on their own. The only question was whether the founders could implement their vision beyond small, specific discoveries in establishing innovation machines.

The Opening (2015-2020)

Nobody planned it this way.

When China's biotech founders launched their companies between 2010 and 2014, the dominant paradigm in oncology was still the small molecule. Decades of accumulated advantage through compound libraries, structure-activity databases, and manufacturing know-how were held by the incumbents. Pfizer, Merck, Roche, and Novartis had spent half a century building moats that seemed unassailable. A rational observer in 2012 might have predicted Chinese biotechs would spend the next twenty years as fast followers, producing cheaper versions of yesterday's innovations.

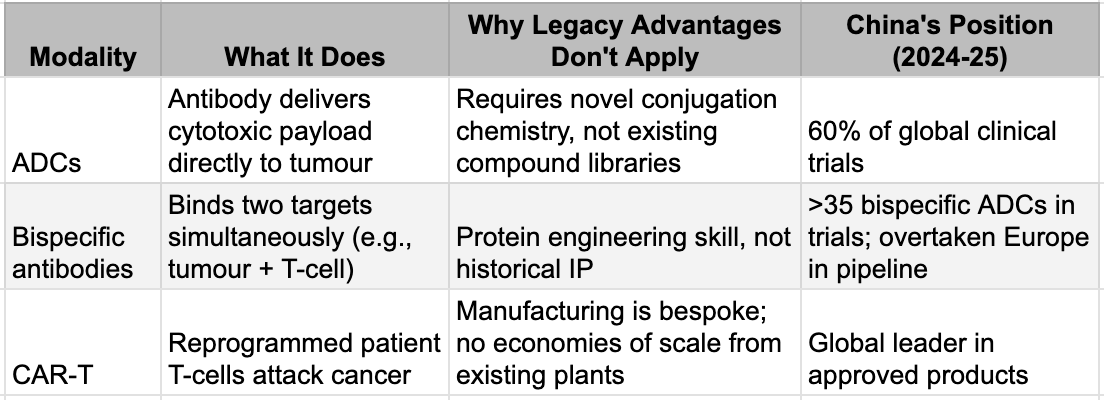

Instead, the rules changed. Between 2015 and 2020, a series of clinical breakthroughs validated entirely new ways of killing cancer cells: antibody-drug conjugates that delivered toxic payloads directly to tumours, bispecific antibodies that could grab a cancer cell with one arm and a T-cell with the other, and CAR-T therapies that reprogrammed a patient's own immune system. These were not incremental improvements on existing drugs. They were new architectures - and crucially, architectures where the incumbents' accumulated advantages counted for almost nothing. Legacy compound libraries were irrelevant. The existing manufacturing infrastructure was wrong. The learning curve reset to zero for everyone.

China's founders had built their companies to compete in the old game. They discovered they had accidentally positioned themselves for the new one. The same capabilities that enabled world-class contract research - protein engineering, antibody development, process optimisation, GMP manufacturing - were precisely what the new modalities demanded. The cost advantages that made China attractive for outsourced research now meant Chinese biotechs could run two or three clinical programmes for the price of one in Boston. The speed that came from dense clinical trial infrastructure meant they could generate human proof-of-concept data while Western competitors were still in preclinical studies. The window was open, and they were standing in front of it.

The New Modalities: Where Incumbency Stopped Mattering

The numbers tell the story. In 2020, Chinese companies accounted for less than 20% of newly registered ADC clinical trials globally. By 2023, the figure was 60%. In bispecific antibodies, China has overtaken Europe as a source of new pipeline drugs. In 2024, mAbs and ADCs licensed from Chinese companies accounted for 89% of all molecule types in cross-border deals, with total deal value three times that of comparable US out-licensing. Big Pharma noticed. In 2025, large pharmaceutical companies spent more than 40% of their deal expenditures on assets originating in China. The preparation had been deliberate. The timing was a gift.

The Factories (2025)

The companies that started with a handful of chemists and a borrowed laboratory now resemble something that hasn't existed in decades: vertically integrated pharmaceutical innovation engines.

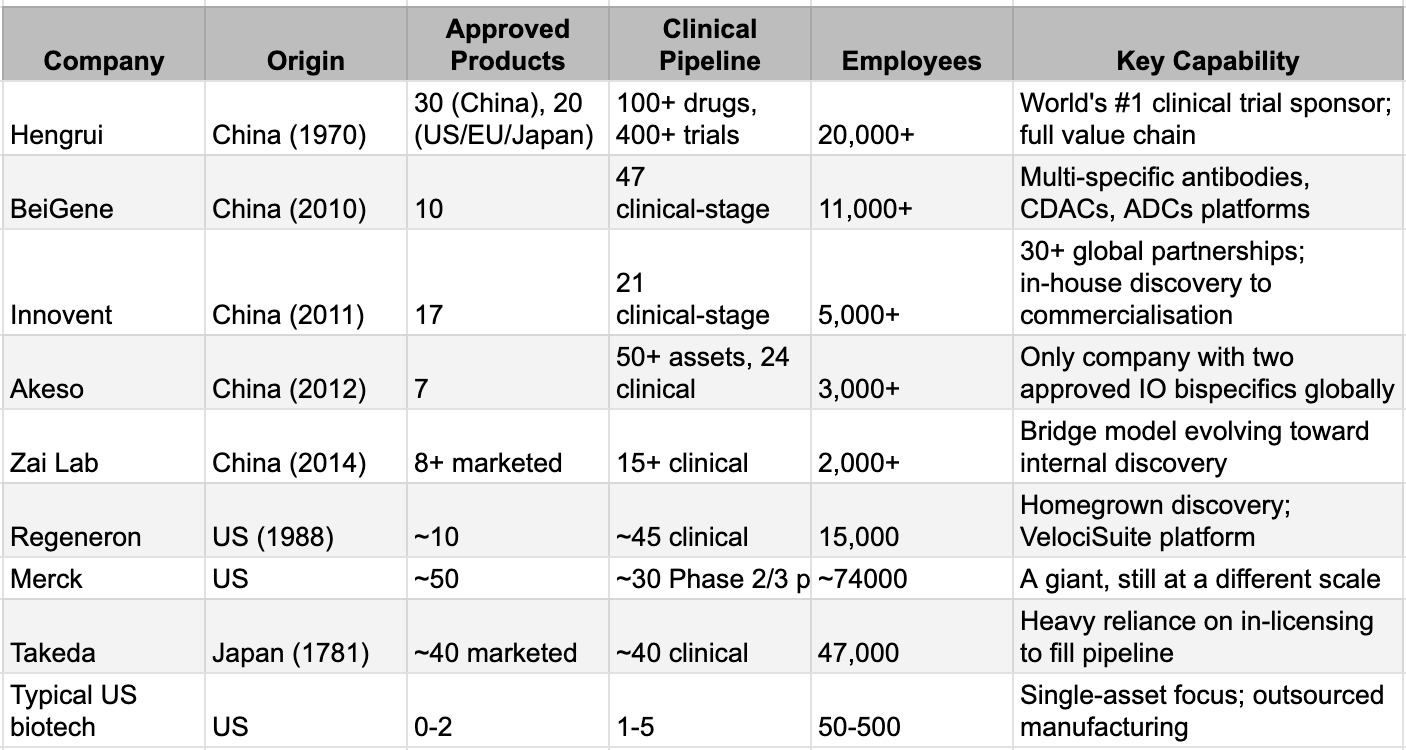

Consider the numbers. BeiGene employs over 11,000 people across five continents, operates one of the largest oncology research teams in the industry, and maintains three distinct platform technologies. Hengrui fields 20,000 employees and 5,600 R&D professionals across 15 global research centres, has commercialised 30 drugs in China and 20 in the US, EU, and Japan, and runs over 400 clinical trials globally, enough to make it the world's top clinical trial sponsor in 2024, overtaking AstraZeneca. Innovent has launched 17 products, with four assets in Phase 3 and fifteen in early clinical development. Akeso, the company that started with less than $3 million and no salaries, now operates 54,000 litres of production capacity, with another 106,000 under construction, and has advanced over 50 innovative assets. These are not venture-backed biotechs seeking to reach proof of concept and sell to a larger partner. These are pharmaceutical companies.

The comparison to Big Pharma is instructive but incomplete. Like the majors, these companies own their entire value chain: discovery, development, manufacturing, clinical operations, regulatory affairs, and commercialisation. Like the majors, they generate revenue from marketed products that fund the next generation of research - the compounding engine that transforms one-off successes into durable franchises. But there's a crucial difference: Big Pharma has spent the past two decades dismantling its internal capabilities. Today, the majors outsource nearly half of all R&D activities. The global CDMO market has grown to over $240 billion precisely because Western pharmaceutical companies concluded that in-house drug development and manufacturing were unprofitable. They sold or closed research sites, outsourced clinical trials to CROs, and transferred manufacturing to CDMOs. The Chinese leaders did the opposite. They built manufacturing before they had products to manufacture. They hired commercial teams before they had products to sell. They kept the capabilities in-house that their Western counterparts were busy outsourcing.

The model differs equally from the Western biotech archetype. A typical American biotech raises venture capital, advances a single asset or small portfolio to Phase 2 data, then either sells to Big Pharma or attempts a high-risk commercial launch with an outsourced infrastructure. The founders exit; the molecule gets absorbed into a larger organisation's pipeline; the learning dissipates. The Chinese leaders rejected this model explicitly. They treated each programme not as a standalone bet but as a node in a learning network where insights compound across the portfolio. The result is something new: organisations with Big Pharma's scale and scope, biotech's speed and focus, and vertical integration that neither model retained.

The proof is in the deal flow. When Takeda needed to fill its oncology pipeline ahead of the patent cliff, it paid Innovent $1.2 billion upfront, plus up to $10.2 billion in milestones, for rights to two late-stage assets and an option on a third. When Summit needed a drug that could challenge Keytruda, it licensed ivonescimab from Akeso for up to $5 billion. When GSK sought to extend its respiratory and oncology pipelines, it paid Hengrui $500 million upfront for access to up to 12 programmes, with potential milestone payments totaling $12 billion. When Merck needed an oral Lp(a) inhibitor, it licensed one from Hengrui for up to $2 billion. In 2025, 35% of all Big Pharma deals originated in China. These are not transactions between a small innovator and a large acquirer. They are partnerships between organisations with comparable capabilities, where the Chinese partner often retains manufacturing responsibility, co-development rights, and board representation. The power balance has shifted.

The Final Test: Graduating from the Foundry (2020–Present)

The movie is nowhere near its conclusion, and no champion has yet been crowned. While China's innovative engines have been refined in the most competitive industrial forge on earth, the world's Big Pharma giants, the Mercks, Roches, and Pfizers, remain the undisputed heavyweights of global commercialisation and foundational science.

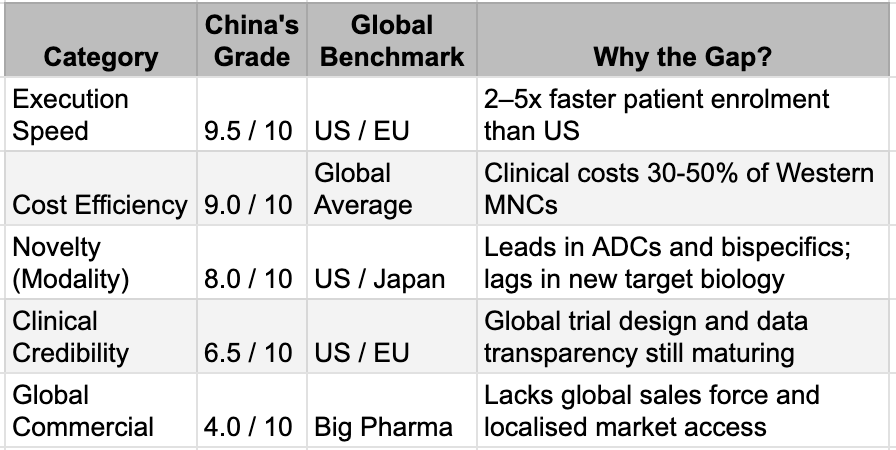

The Opening gave China a seat at the table. But the final judgment occurs in what Bruce Lee called the "mirror room," where a drug must not only demonstrate remarkable data in a local trial but also survive the rigorous scrutiny of the FDA and the complex realities of multi-regional clinical trials. China has moved from Innovation 1.0 (fast-following) to Innovation 2.0 (quality-driven development), but it remains a work in progress. We see the potential for global best-in-class status in drugs such as ivonescimab, which nearly doubled progression-free survival compared with Keytruda in head-to-head competition. But until these results are replicated across diverse global populations and secured by multi-billion-dollar commercial launches, the underdog tag will remain.

The Innovation Scorecard

Conclusion: The Silent Pivot

In our previous note, we discussed the role played by policy change. But, innovations do not happen just because of rule changes. The rise of the Chinese pharmaceutical industry was not an accident of policy alone, nor was it a sudden stroke of scientific genius. It was a 25-year structural transformation that relied on a host of accidental and deliberate factors. Consider what it would take to rebuild this from scratch: the tacit knowledge accumulated across thousands of manufacturing campaigns, the clinical trial infrastructure that now enrols patients faster than anywhere else on earth, the vertical integration that Big Pharma spent two decades dismantling. The stakeholders can now reap the climactic benefits of this long backstory.

Markets and commentator communities around the industry are far from convinced. A large part needs a proof in approvals from Western regulators and actual revenues rather than evaluating the establishments for the capabilities they have built. The structures that are built indicate consistent and durable success in revenue and innovation approvals. For now, a company that defeats Keytruda in a head-to-head trial but has not yet filed for FDA approval is dismissed as unproven. A platform that out-licenses $10 billion in assets is valued as if those assets might never reach patients. This is the credibility discount that could repeatedly come under pressure in the coming years.

This is the gap between what has been built and what has been recognised. The preparation was deliberate. The timing was fortunate. The outcome remains unwritten. But, the underdogs have already entered the ring.

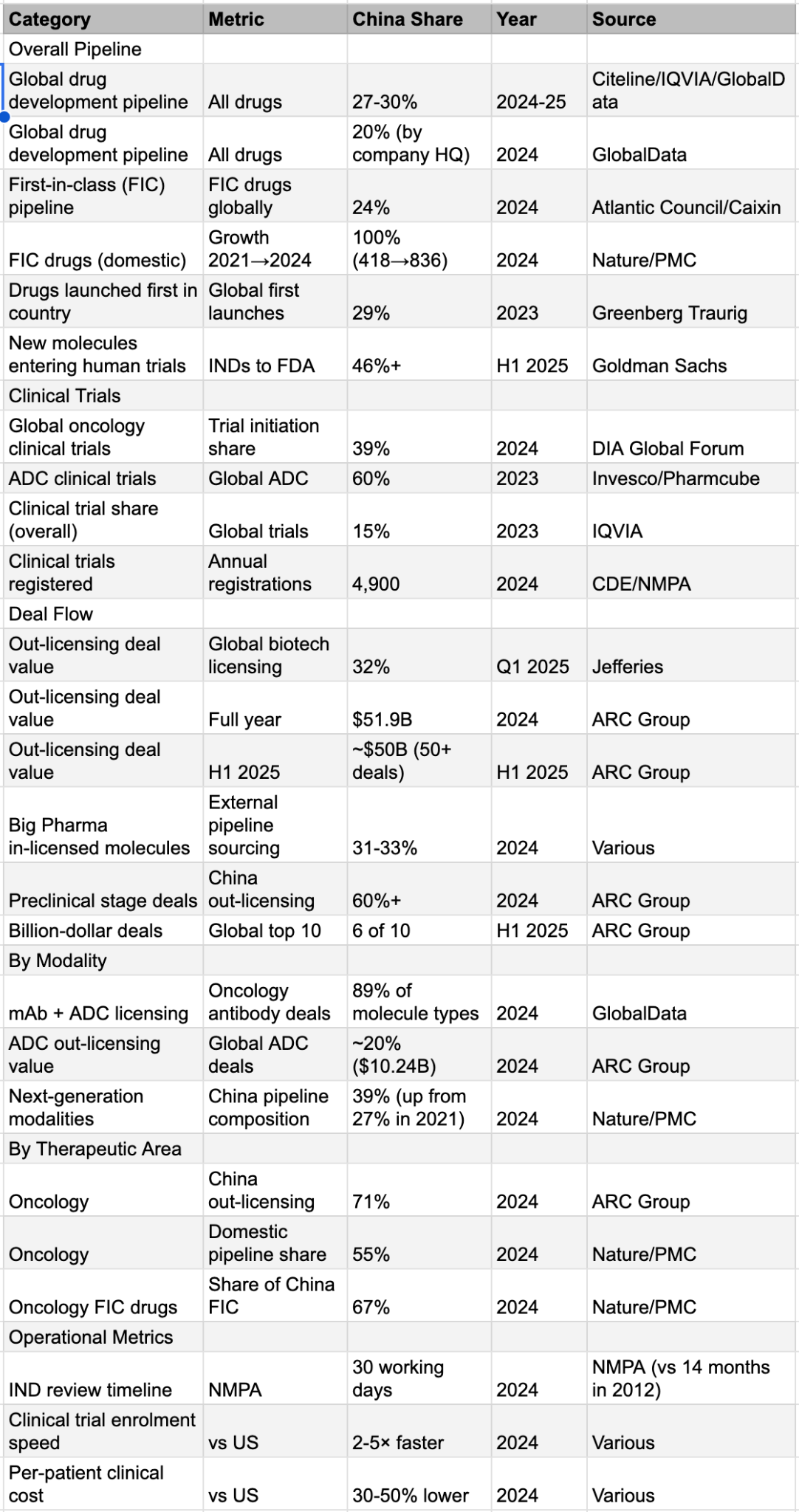

Appendix: China’s Share of Global Pharma Innovation