The defining economic shift of the generative artificial intelligence era is not the creation of new digital intelligence, but the rapid commoditization of human ideation. For the past three years, we have watched this reality ripple outward from the epicenter of software development, where the cost of generating foundational code continues to collapse and where the domain of human dominance and brilliance continues to shrink. At various times, we have feared the declining value of cognitive aspects bleeding into chip design, robotics, and autonomous driving, although these are fields where markets are yet to share our opinions the way they have begun to across service domains in recent weeks.

The segments of the global economy that previously represented the absolute forefront of human cognitive endeavor are systematically facing intense margin pressure as machine intelligence assumes the burden of generating novel ideas. The economic value within these industries is not vanishing, but it is migrating aggressively toward physical chokepoints, proprietary datasets, and real-world execution layers. We are witnessing the repricing of the blank page, and another segment where this dynamic is becoming more visible, or more consequential, is in the global pharmaceutical industry.

Drug discovery is now showing the same structural forces. The cost of generating a new molecular candidate is falling. The pace at which competing teams can converge on the same biological target has accelerated dramatically. And the ability to replicate another team's breakthrough, what we have called instant copyability since we started publishing, is emerging in ways that would have been unthinkable five years ago. The replication cycle itself is compressing. Few people in the investment world have discussed the massive implications of rising copyability and the attendant herding.

The evidence in drug discovery is not as indisputable as what we witnessed in software or what is currently unfolding in semiconductors. The timescales are different, the biology is harder, and the full data will take years to arrive. But the overwhelming pattern suggests that in drug discovery, the initial phases of ideation and the analysis phases are where commoditization is most visible, while value is shifting decisively to the middle and later stages, to Phase 2 clinical proof, to manufacturing scale-up, to the physical execution that no algorithm can shortcut. One can wait for the comprehensive evidence to emerge. Or one can observe what is already happening and apply logic rather than habit. This article does the latter.

The DMTA Framework and Pharma's Historic Bet

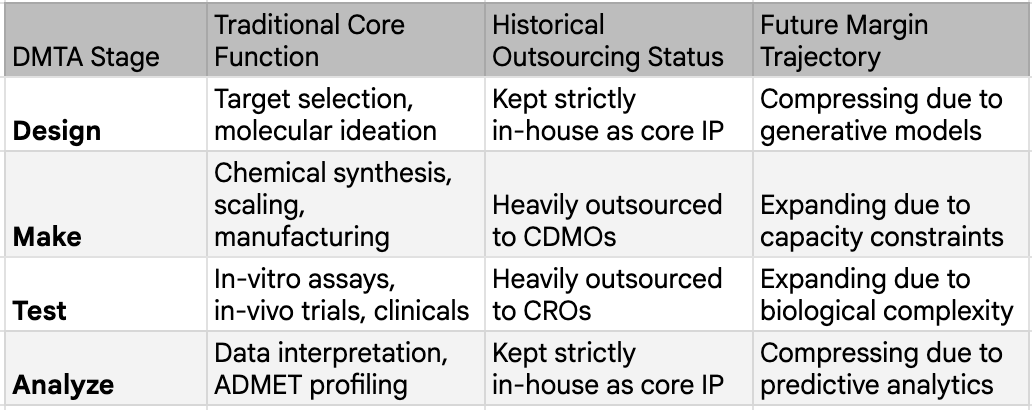

To understand why the impending commoditization of cognitive work is so disruptive to the pharmaceutical business model, one must first examine the established architecture of how a drug comes to market. The industry operates on a universal, sequential workflow known as the DMTA cycle, which stands for Design, Make, Test, and Analyze.Design a molecule, Make it in the lab, Test it in biological systems, and Analyze the results to decide what to try next. This cycle repeats hundreds or thousands of times before a drug candidate emerges from preclinical work. After that comes the clinical gauntlet, Phase 1 safety trials, Phase 2 proof-of-concept, Phase 3 registration trials, followed by manufacturing and commercialization.

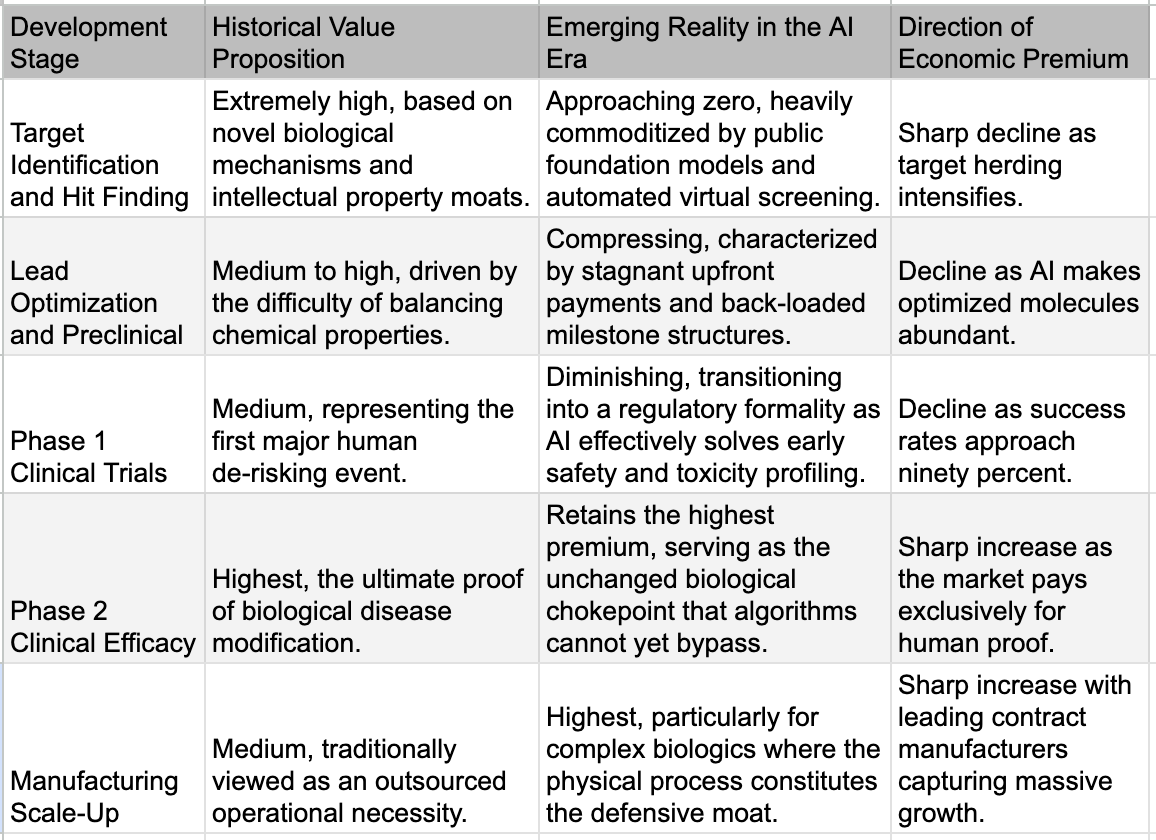

Historically, the overwhelming majority of prestige, capital, and margin accrued directly to the Design and Analyze stages. These segments constituted the highly specialized "office work" of pharmacology, where immense libraries of proprietary chemical compounds were guarded as corporate crown jewels and armies of PhD-wielding medicinal chemists relied on decades of accumulated human intuition to sketch out potential molecular candidates.

Because the generation of ideas was the accepted bottleneck of the entire enterprise, the major pharmaceutical conglomerates made a highly specific, generational strategic bet regarding where their internal capital should be deployed. They structured their organizations to aggressively retain the high-margin, high-value cognitive activities of Design and Analyze, treating these functions as the irreplicable core of their business. Conversely, the supposedly lower-margin, highly repetitive physical work associated with the Make and Test stages—the actual chemical synthesis, the routine laboratory assays, and the vast logistical undertaking of human clinical trials—was systematically outsourced. This work flowed steadily outward over the decades, first to specialized contract research organizations (CROs) and contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) in the West, and eventually offshore to deep labor pools in Asia.

This strategic bifurcation perfectly mirrored the structural evolution of the broader technology sector over the same period. Just as semiconductor companies like AMD and Nvidia eagerly transitioned to "fabless" models to focus purely on chip architecture while outsourcing the messy, capital-intensive physical fabrication to Asia, pharmaceutical companies sought to become asset-light intelligence hubs. The prevailing management theory across all sectors of the Western economy dictated a simple mandate: keep the smart work, outsource the hands work. It was a perfectly rational economic strategy for a world where cognitive power was scarce and human labor was abundant.

The profound vulnerability of this strategy is only now being exposed by the arrival of generative models. The fundamental premise of the outsourced model relied on the absolute assumption that the cognitive layers of the DMTA cycle would forever remain complex, proprietary, and uniquely human. Now that the "smart" work is actively commoditizing at an unprecedented rate, pharmaceutical companies are awakening to a landscape where the specific capabilities they spent two decades outsourcing have unexpectedly become the post critical, capacity-constrained moats in the entire ecosystem.

The New AI is Not the Old AI

For our long-time readers, these sub-section titles may be familiar from the technology segments we were writing for in 2023 and onwards. It is true that “artificial intelligence” has been used in pharmaceutical research for years, but categorizing the current technological shift as a mere continuation of past trends is a serious analytical error. The distinction matters because skeptics routinely cite the mixed clinical track record of "AI-discovered drugs" to dismiss the entire thesis. They fail to recognize that technologies used today are similar to those even three or four years ago in name only.

The algorithms deployed prior to 2023 were fundamentally evolutionary tools. Earlier iterations of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, narrow neural networks used for basic molecular docking, and early predictive screens for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) were largely designed to help human chemists filter their existing ideas slightly faster. The popular press and pharma marketing departments conflated this with the generative AI revolution, creating expectations that were impossible to meet.

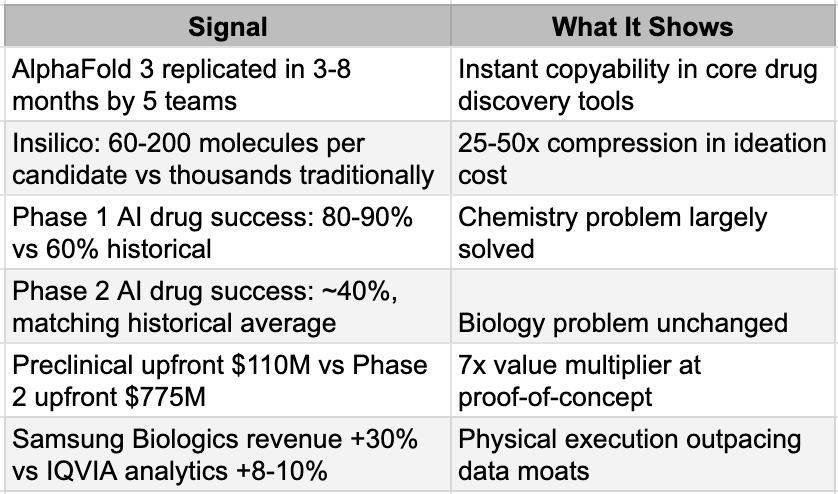

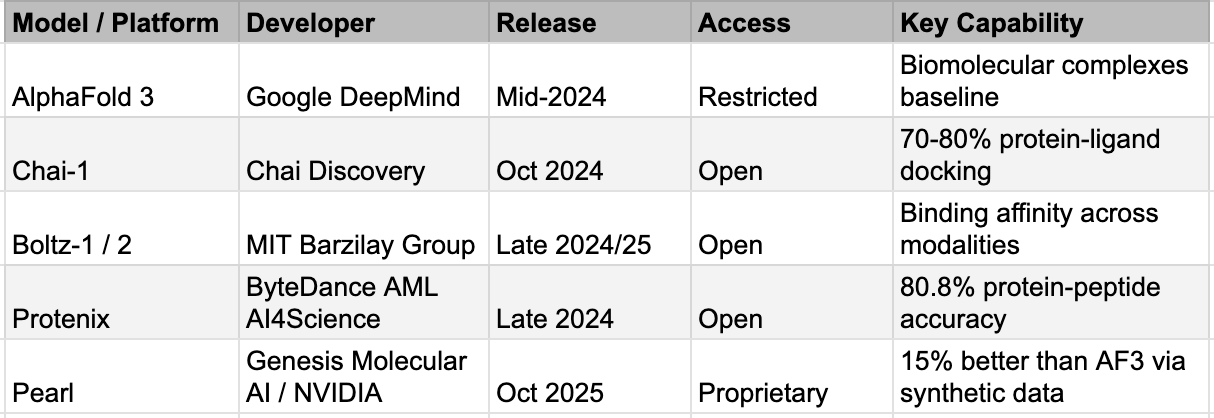

The post-2023 wave of technology, driven by massive biological foundation models, generative molecular design utilizing advanced diffusion models, and the ability to conduct virtual screening across multi-billion-compound libraries in days, is categorically revolutionary. Biological foundation models like ESM3 and Evo 2 now operate across DNA, RNA, and protein simultaneously, the biological equivalent of a multimodal LLM. Generative molecular design has moved from variational autoencoders and GANs, which produced limited novelty, to diffusion-based models that generate genuinely novel chemical matter. Virtual screening has scaled from millions to billions of compounds: Enamine's REAL Space alone contains sixty-nine billion synthesizable molecules. And structure prediction, once a grand challenge that consumed entire scientific careers, can now be run for pennies. The AlphaFold 3 replication story is worth repeating: what took Google DeepMind years to build was reproduced by five teams in months as mentioned above, including Protenix from ByteDance and Boltz-1 from MIT, with Chai-1 matching its ligand prediction accuracy at 77% versus AlphaFold 3's 76% on the PoseBusters benchmark. We discuss the factors causing this and the implications in more detail in the next section as well.

Instant Copyability around AlphaFold3

This generation of AI is changing the actual mechanics of early drug discovery. Insilico Medicine disclosed that their twenty-two preclinical candidate nominations between 2021 and 2024 required only sixty to two hundred molecules synthesized per project, taking twelve to eighteen months from initiation to candidate selection. The traditional process synthesized five to ten thousand compounds over three to five years. That is a twenty-five to fifty-fold compression in the Design phase. The cost of an idea, in the most literal sense, has collapsed.

The Era of Instant Copyability in Drug Discovery, too

This is the natural next question: "OK, the new AI is powerful — so what does it enable?" Answer: everyone converges on the same targets at digital speed. Time to revisit the copyability in detail for the implications.

The traditional pharmaceutical business model relied heavily on the absolute defense of the first-mover advantage. Historically, if a company discovered a novel molecule for a validated biological target, the sheer manual difficulty of medicinal chemistry provided a multi-year moat before competitors could synthesize viable, structurally distinct alternatives. Today, the moment a novel target is validated or a promising molecular structure is hinted at in literature, the global pharmaceutical ecosystem can instantaneously generate thousands of highly optimized, chemically viable alternatives that deliberately bypass existing intellectual property. We are witnessing the sudden death of the chemical moat, replacing a paradigm of deliberate discovery with one of instant, algorithmically driven copyability.

This is the result of the new AI. What used to take years of painstaking analog synthesis and freedom-to-operate analysis now happens at digital speed. Publish a novel chemotype for a hot oncology target, and within days, generative diffusion models and reinforcement-learning optimizers are already exploring adjacent chemical space, scoring millions of variants for affinity, synthesizability, and patent circumvention. The old proprietary hit matter evaporates because anyone with a GPU cluster and access to the Enamine REAL virtual library of 69 billion compounds can run the same, or at times even superior, screen and surface overlapping hits in hours.

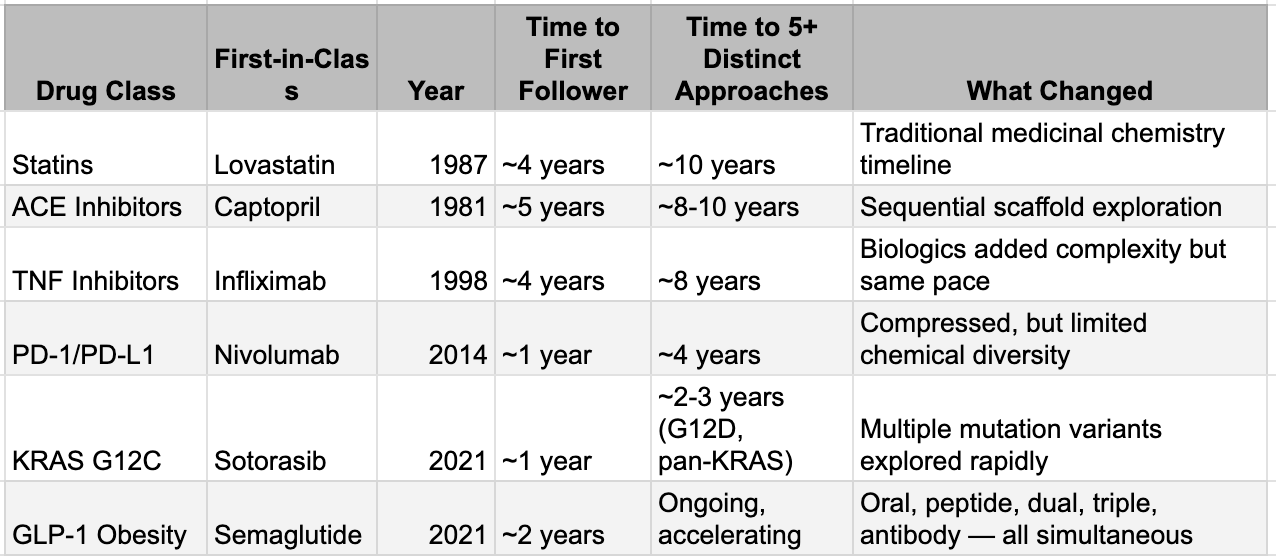

This is not theoretical. The GLP-1 wave offers the clearest live demonstration. Semaglutide’s structure became public with its 2021 approval; by 2023, tirzepatide (a dual agonist) was approved, and generative models have since produced dozens of dual- and triple-agonist analogs now sitting in pipelines worldwide. The fast-follower cycle that once stretched to four or five years for statins or ACE inhibitors has collapsed to under 18 months. KRAS G12C tells the same story: sotorasib approved in 2021, adagrasib followed in 2022, and by 2025 five or more next-generation agents (including Roche’s divarasib with superior response rates) were already in late-stage trials. Each successive wave has shortened the replication timeline; generative AI is simply turning the crank from years to months.

This is not simply fast-follower pharma behavior with big budgets. The distinguishing feature is the range of chemical approaches pursued simultaneously and the compression of the exploration timeline. Generative molecular design tools allow teams to explore vast regions of chemical space around a validated mechanism, proposing structurally distinct but functionally equivalent molecules that would have taken years of manual medicinal chemistry. Where a traditional fast-follower program might explore one or two alternative scaffolds over several years, AI-augmented teams can explore dozens of scaffolds in months. The result is that the window during which a first-in-class drug enjoys a meaningful competitive moat, the period where its discoverer can extract premium economics, is shrinking dramatically.

The patent landscape adds another dimension. IBM Research's PatCID system, published in Nature Communications in August 2024, extracted eighty-one million chemical structure images and fourteen million unique structures from global patent databases spanning the US, Europe, Japan, Korea, and China since 1978. It outperforms Google Patents, SureChEMBL, Reaxys, and SciFinder on retrieval accuracy. When you combine this kind of automated patent intelligence with generative molecular design, you create something that did not exist before: the algorithmic capability to map a competitor's patent claims, identify the structural boundaries of their protection, and design around them systematically. What previously required a team of patent attorneys and medicinal chemists working for months can increasingly be done computationally in weeks. The economics of pharmaceutical intellectual property, one of the deepest moats in all of business, are being quietly rewritten.

The aggregate evidence is visible at the industry level. The number of truly novel biological targets entering drug discovery pipelines has reportedly compressed from approximately one hundred per year to around thirty, even as total pipeline volume has nearly doubled. AI is not generating more targets. It is making everyone faster at chasing the same validated targets. The result is herding, a concentration of competitive effort on proven biology, with ever more molecules competing for the same therapeutic space. China's emergence as an "innovation supermarket" is the national-scale expression of this force: 639 first-in-class candidates since 2022, a 360 percent increase from the prior baseline, with $135.7 billion in outbound licensing deals in 2025 alone. When a country can mass-produce preclinical candidates at this pace and export them to Western pharma, the scarcity premium on early-stage ideas does not just erode. It collapses.

While nimble AI biotechs use generative models and PatCID’s 14-million-structure patent map as a sword to carve out clean design-arounds in days, the incumbents have quietly flipped the identical tools into a shield. Big Pharma now feeds diffusion and reinforcement-learning engines with their own Markush claims and instructs them to enumerate thousands of computationally validated “species” within every broad genus, flooding the USPTO and EPO with pre-emptive, AI-generated variants that turn a single patent into a volumetric thicket. The result is paradoxical: IP becomes both easier to attack (because every molecule is now machine-searchable) and harder to navigate, pushing the decisive battle even further downstream to the teams that can physically manufacture at scale and litigate through the resulting legal fog.

When The Interpreters Lost Their Edge

The Design phase gets all the attention, but the quiet collapse is happening one step later in the Analyze phase, where experienced scientists interpret experimental results and decide what to do next. This was never glamorous work. It did not make press releases. But for decades, it was the domain where accumulated expertise created genuine, durable competitive advantage, and its erosion may matter more for the economics of drug discovery than anything happening in molecular design.

At the preclinical level, the analysis moat was built on the intuition of senior medicinal chemists, who were generally scientists with decades of experience who could look at a set of structure-activity relationship data and see patterns that junior colleagues could not. "The methyl group here kills potency but improves metabolic stability, so try a cyclopropyl instead." This was not guesswork. It was pattern recognition honed across thousands of molecular iterations over a career, and a pharma company with fifty such scientists had a meaningful edge over a startup with five. It was also, unfortunately for the people who built those careers, exactly the kind of pattern recognition that machine learning does well. Modern models trained on large SAR datasets encompassing millions of compound-activity pairs across decades of published and proprietary data can now propose the next round of molecular modifications with a sophistication that matches or exceeds individual chemist intuition. They do it faster, they do it without the cognitive biases that lead experienced chemists to revisit familiar chemical space, and they do it at a marginal cost approaching zero. The preclinical analysis moat is not eroding. For practical purposes, in many therapeutic areas, it is gone.

One level up sits clinical data analysis: the expensive, specialized work of interpreting early clinical trial results. Reading a Phase 1 pharmacokinetic study to determine whether enough drug reaches the target. Parsing safety signals to decide whether an elevated liver enzyme is a class effect or a molecule-specific liability. Figuring out whether a Phase 2 trial failed because the drug did not work or because the trial enrolled the wrong patients, used the wrong dose, or measured the wrong endpoint. This required a different kind of expertise: clinical pharmacology, biostatistics, and regulatory strategy. It was slow, expensive, and genuinely scarce. This is an area under AI attack as well.

The third and deepest analytical layer is the one where AI has made the least progress, and it may be the most important. Translational biology, or the ability to connect what happens in a preclinical model to what will happen in a human patient, remains stubbornly resistant to computational approaches. The core judgment call is deceptively simple: does this animal model actually predict human efficacy for this mechanism? The answer is almost never straightforward. It depends on decades of accumulated institutional knowledge about which mouse models reliably translate for which disease areas, which biomarkers are predictive versus decorative, and which historical failures carry lessons that have never been formally documented in any database. This is knowledge that lives in the heads of experienced translational scientists, often learned through painful Phase 2 failures that companies are reluctant to publish. It is sparse, biased, and largely inaccessible to training algorithms. Whether foundation models trained on genomic and real-world evidence data can eventually crack this layer is the single most important open question for the future of AI in drug development. If they can, cognitive value re-differentiates, and the commodity narrative weakens. If they cannot, the Phase 2 wall holds, and value continues migrating to physical execution.

The wall, and the money that piles up behind it

If generative AI has compressed the Design phase by twenty-five to fifty-fold and is systematically eroding the Analyze layer, the obvious question is: where does value actually sit now? The answer is brutally specific, and a single dataset tells the story. A 2024 study published in Drug Discovery Today, drawing on BCG's analysis of 114 AI-native biotech companies, found that AI-discovered drugs achieve Phase 1 success rates of eighty to ninety percent, dramatically above the sixty percent historical industry average. But their Phase 2 success rate sits at approximately forty percent, indistinguishable from historical norms. AI has solved the chemistry problem. It has not touched the biology problem. Phase 1 is fundamentally a chemistry test: is this molecule safe, and does it reach its target? AI excels here because the data is abundant, the physics is well-understood, and the prediction task is clean. Phase 2 is a biology test: does intervening in this pathway, in this population, produce a clinically meaningful outcome? The biology is stochastic, poorly mapped, and riddled with emergent properties that no model trained on existing data can anticipate. No AI-discovered drug has received FDA approval as of late 2025, despite seventy-five having entered clinical trials. The wall holds.

The deal economics reflect this with surgical precision. JPMorgan's 2025 biopharma licensing data shows median preclinical upfront payments of $110 million versus Phase 2 upfronts of $775 million, a seven-fold multiplier. That single ratio IS value migration expressed in dollars. The structure underneath is even more telling: upfront payments represent only seven percent of total deal value across 2023, 2024, and 2025, with ninety-three percent sitting in milestone payments overwhelmingly tied to clinical proof. The market no longer pays for ideas. It pays for proof. And while preclinical absolute upfronts actually rose in 2025, this likely reflects intensifying competition for the best AI-generated assets rather than a contradiction of the thesis: when everyone can generate candidates, the bidding war shifts to whichever candidate looks most likely to survive Phase 2, not to the cleverness of its molecular design.

The physical execution layer is where this repricing shows up most clearly in corporate performance. Samsung Biologics reported 2025 revenues of $3.1 billion, up 30% YoY. Lonza's integrated biologics segment grew 32%, with 70% of its revenue coming from Phase 3 and commercial manufacturing, aka the work that sits squarely on the other side of the Phase 2 wall. These are not companies riding hype cycles. They are filling bioreactors with molecules that survived the gauntlet, and the demand for their capacity is structural. These companies are expanding capex aggressively. Their capital cycle tells you where the industry believes scarcity will persist for the next decade.

The distinction between types of contract research organizations matters here and is almost always missed. Discovery CROs — those providing medicinal chemistry, hit finding, and lead optimization for hire — face structural pressure as AI commoditizes the cognitive work they sell. Why pay a premium for human-led lead optimization when an AI pipeline produces equivalent candidates faster? Development CROs — those managing clinical trials, safety studies, and regulatory submissions — benefit from the flood of candidates now surviving into clinical development. More ideas reaching Phase 2 means more trials to run, more patients to enrol, more regulatory dossiers to compile. The CRO market is not a monolith. It is splitting along the same cognitive-versus-physical fault line as the broader industry, and investors who treat it as a single sector are missing the divergence that matters most.

The picture is not clean, and intellectual honesty demands saying so. If the Phase 2 wall holds indefinitely, AI's role in drug development could plateau, and some of the value-migration forces described here could partially reverse. The BIOSECURE Act, signed into law in December 2025, adds a further wrinkle by creating artificial scarcity in non-China CDMO capacity, manufacturing a policy-driven moat that amplifies physical chokepoints regardless of the underlying technology dynamics. And the strongest counterargument to the entire thesis deserves tracking: if post-2023 foundation models trained on genomic and real-world evidence data eventually raise Phase 2 success rates above historical averages, cognitive value re-differentiates, and the commodity narrative needs revision. That data does not yet exist. The real generative AI vintage has barely entered Phase 1, and meaningful Phase 2 results are years away. But the direction of travel in deal economics, in CDMO order books, and in the seven-fold gap between preclinical and Phase 2 valuations is already legible. The market is not waiting for academic proof. It is repricing now.

The Age of Abundant Cognition

The forces reshaping drug discovery are not unique to pharma. They are an expression of something broader: the arrival of abundant cognition. When generative models can produce code, design molecules, draft legal arguments, analyze financial statements, and generate creative content at near-zero marginal cost, every industry built on the scarcity of cognitive work faces the same structural question. Where does value actually reside when ideas are cheap?

The answer, consistently across every domain we have examined, is that value migrates to whatever remains scarce. In semiconductors, it is manufacturing capacity and accumulated process knowledge. In drug discovery, it is Phase 2 clinical proof and GMP manufacturing capability. In the broader economy, it may increasingly be physical execution, human judgment in novel situations, and the trust that comes from demonstrated real-world outcomes rather than predicted ones. The transition will not be comfortable. Medicinal chemists whose careers were built on the intuition of "try cyclopropyl" are processing the same identity disruption as software engineers watching AI write their code. Companies that built their strategies around data moats are discovering that those moats are shallower than they believed. Western firms that outsourced physical capabilities for decades now need them back and cannot rebuild them overnight.

But the underlying reality is not going away. Global cognitive power has increased materially and permanently with the arrival of these models. The drug discovery industry is not the first to feel it and will not be the last. Whether one looks at finance, industrial processes, professional services, or labor markets broadly, the same analytical challenge applies: recognizing where cognitive abundance is changing the rules, where physical scarcity is reasserting itself, and how the value chain is being redrawn. The organizations and investors who see this pattern early, without waiting for comprehensive data confirming the change and debunking historic “truths,” will likely avoid unpleasant surprises. As we said multiple times before, we live in the world of billions of super-Einsteins. And as a result, Einsteins are losing their value.