Important: We have long believed that the GenAI era has tipped the balance between hardware/software. This piece is not another repeat of the theme. This note is not an attack on chip design. Chip design is hard. One only needs to glance through any NVIDIA announcement to appreciate how elite it is. It is one of the highest forms of modern engineering. But our claim is still simple: manufacturing is harder. The manufacturing side has been treated as the “lesser” sibling for decades. Lower multiple. Lower prestige. More cyclic. Less scalable. We think that, as with the balance between hardware and software, the balance between Chip Design, which we call Hardware’s Software or “Office” work, and Chip Manufacturing, aka “Plant” work, has shifted and is difficult to ignore.

Points Pessimists Miss

There are two major types of pessimists: the survey pessimists and the ROI pessimists. They both miss important, all-too-visible points.

As discussed in last week's Silicon Shock report, the survey crowd’s blithe ignorance of the actual usage explosion is counterproductive. They repeatedly chant a middle-management survey portraying a lack of AI enthusiasm. They find confusion. They find uncertainty. They conclude: AI adoption is slow. But they miss what is happening outside the conference room. Four billion people now use a new way of inquiry. Not search. Not browsing. Conversation. This is not a marginal shift. It is a change in how humans interact with machines. And it requires different hardware. Token demand, a highly contentious measure, grew over 40 times in 2025. The silicon required is not the silicon that exists. And, the world is not going back, irrespective of what some surveyors may conclude.

What the ROI people have been missing, something we have said since we started writing in 2023, is that there is a lot of money being made. It is just not made where they are used to looking. This is the problem with the "$600 billion question."

As we have said from our earliest thesis, as the instruction language between us and the machine changed from Python and Java to human languages like English and Gujarati, the software segment entered an era of extreme abundance. Applications can do a lot. But they no longer have the business model they used to have in previous decades.

This has led us to see many different things over the years. We see the commoditization of ideation. In the Internet era, investors could look into founders’ eyes and invest based on the power of ideas, narratives, trust, and network effects. Somehow, the power of such business foundations has waned. Whether it is in robotics or in typical technology, the ideation segment is the one getting commoditized.

With the global investor community still in the previous wave of investing, the transition to a new way has caused anguish. The hardware segment is not intuitive. It cannot be understood through presentations, stories, or even observations. Deals and private transactions are fewer. The simple point is that the hardware segments continue to make merry, and they can even do so if the subsequent layers feel a crunch.

None of the above means all is well. Absolutely, everything skeptics point out is right in some contexts and some corners. Without a doubt, because of the excesses in the application layer and the nature of hardware capital expenditure, there will be cycles. But if some of the companies funded at extremely low cost of capital or with high valuations today are unable to sustain themselves, the hardware segment will certainly use its own resources to set up alternative segments. If end-demand exists, as we believe it does, and the hardware segment is making more than adequate money, the conduits will be sustained even at a loss for the AI world to keep developing, notwithstanding frequent gyrations. Some will call them circular transactions. Some others will see them as business development arrangements, like loss-making marketing campaigns that are not necessarily without utility.

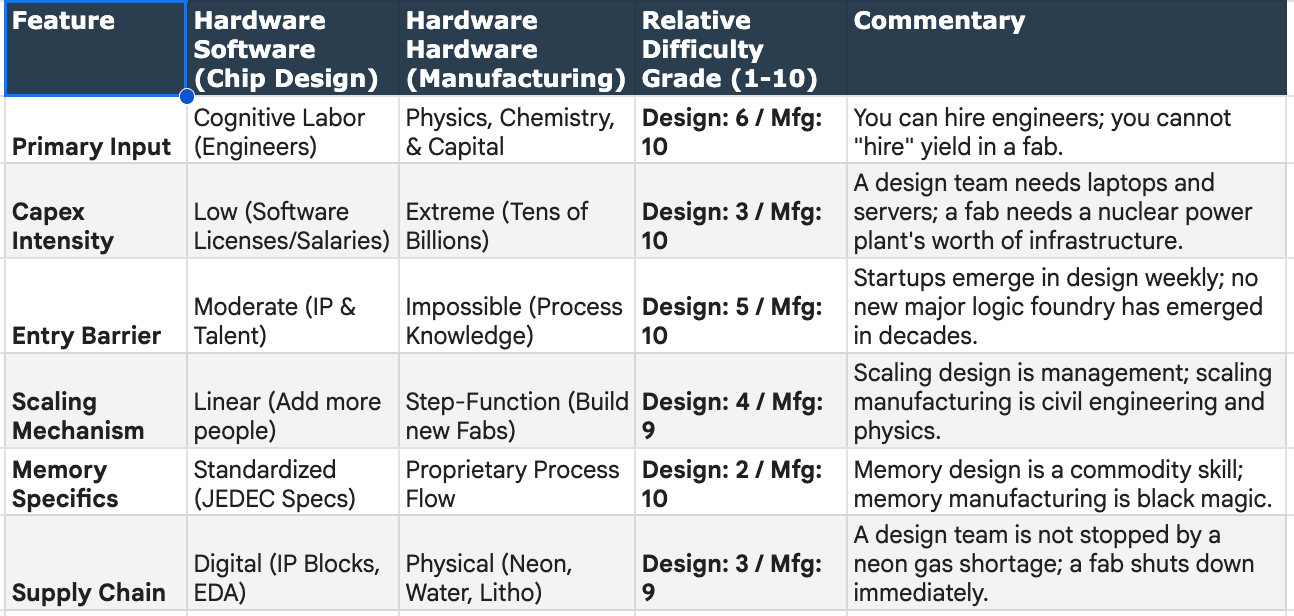

The point of this note, after the necessary preamble above, is different. As we never tire of saying, the hardware segments are difficult to understand. And, they have their own nuances. We need to focus on the biggest division within the hardware layer to understand where the sands are shifting in 2026. For this, we must distinguish between hardware that is true hardware (manufacturing) and hardware that is actually software (design).

Plants vs Offices

The hardware segment can be roughly split into manufacturing and design. Design segment includes, if not otherwise referred to, fabless, chip design, or ASIC. It has many different forms and aims. But this is where you have "office" people working. They build and design on computers. They write RTL code in Verilog. They run it through EDA tools from Synopsys and Cadence. They simulate, verify, iterate. Then they send a file to a foundry and wait. This is what we call Hardware’s Software. This segment includes famous names like NVIDIA and AMD,

The second part is real manufacturing. This is Hardware’s Hardware. Chip manufacturing means fabs and cleanrooms. Thousands of process steps. Atomic-level precision. Engineers work like blue-collar workers. Assembly lines of the mind. High-qualification talent willing to work shifts, follow procedures, and operate as cogs in a machine. This is what countries outside North Asia abandoned long ago.

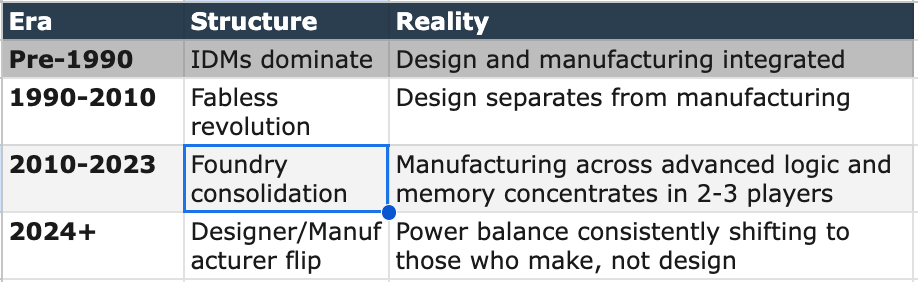

The "Fabless" revolution in the 1990s allowed most companies to focus purely on architecture. They outsourced the messy, capital-intensive manufacturing work to foundries. The Integrated Device Manufacturer (IDM) model has effectively disappeared at the leading edge. Many companies still known as IDMs are mostly just designers. Their manufacturing is either non-existent or no longer cutting-edge.

If one keeps it brutally honest, advanced chip manufacturing is effectively only happening in cutting-edge foundries and memory companies. And the names can be counted on the fingers of a hand: TSMC, Samsung, and Intel in foundries, and SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron in memory. Samsung’s appearance on both lists ensures we do not need to trouble the second hand's fingers.

This split has long existed. But the balance of power within it has evolved. The Silicon Divorce historically allowed Fabless to be “asset light.” Foundries were “utilities.” The design side got glamour. The plant side got cyclicality. The multiples told the story.

Now the story is changing. And one will need to observe many of the arguments below closely before deciding how much of the change is long-term secular.

Erosion of the “Office” Power

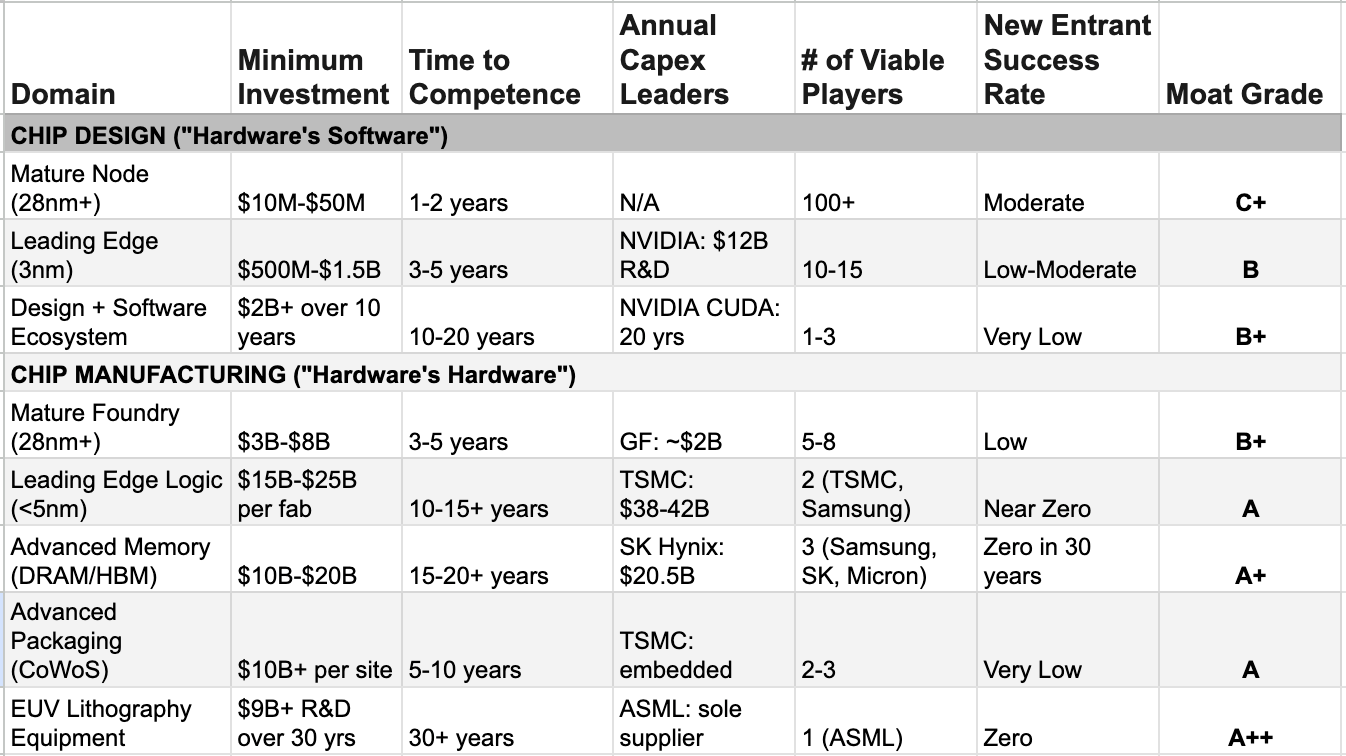

We must repeat: Design is not easy. Creating a cutting-edge chip requires thousands of engineers, years of accumulated innovation, access to expensive Electronic Design Automation (EDA) tools, and collaboration with many other complementary designers. As real as designer barriers are, and as secure as the best producers, like NVIDIA’s products are, chip design is fundamentally a problem that time, capital, and talent can solve to a rising degree. The grades in the tables below should be read for comparative purposes and not absolutely.

As we wrote in the 2026’s Real Chip War piece, almost every major global giant is embarking on chip design, believing that with manageable time, cost, and effort, they can produce competent, internally designed chips that will help their overall businesses. None has so far embarked on meaningful manufacturing plans because the barriers are different.

Manufacturing mastery is path-dependent, even if not unique. They cannot be bought. GlobalFoundries spent $30 billion. It struggles beyond 7nm. Intel spends $26 billion per year and continues to lag. Samsung’s recent struggles in both HBM and foundries are other examples. China has thrown unlimited resources at the problem. It remains stuck at 7nm without EUV. The money does not solve it.

Burn J. Lin, the father of immersion lithography, said it plainly: knowing is not enough. You must produce. Cutting-edge manufacturers’ advantage lies not in the mind of a single strategist, and it cannot be adequately explained in keynote speeches. It is in the seamless coordination of mass-production teams.

The knowledge compounds both in design, as evidenced in every new generation of NVIDIA innovations, and in manufacturing. But the compounding is far more advanced in the latter. Each process node builds on the last. TSMC's 2nm benefits from lessons learned at 3nm, 5nm, 7nm, all the way back to 250nm. A new entrant cannot skip many of these steps. As a result, in the Angstrom era, aka nodes labeled 2nm and below, mastery involves physics and capital challenges that have reduced the playing field to a singularity.

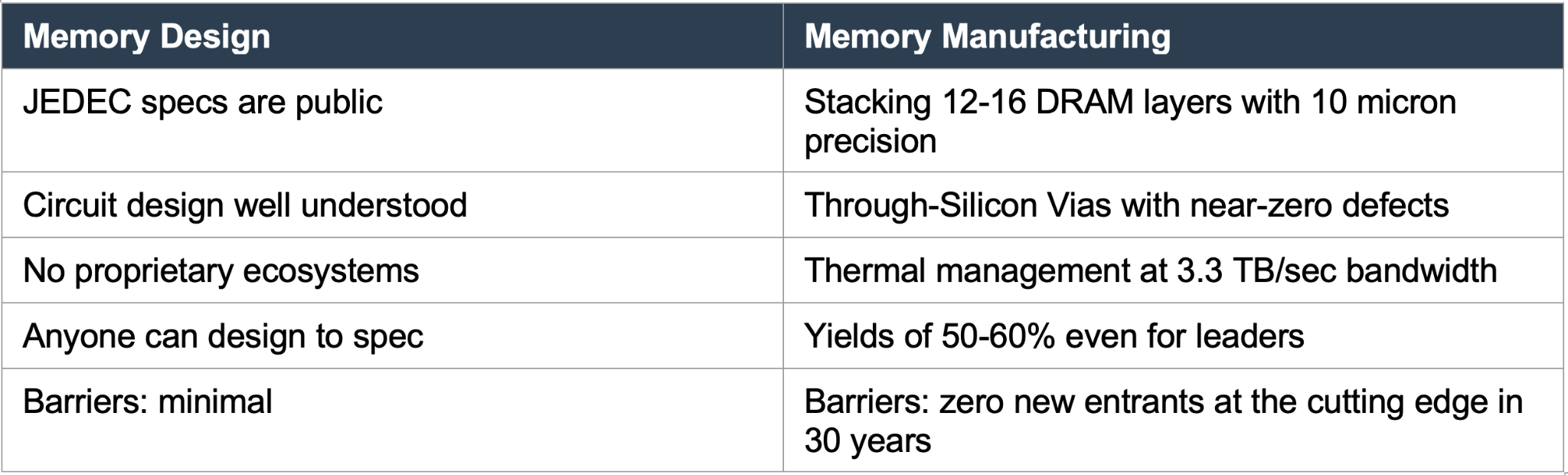

Memory: Illustration of “Plant” Fortress

Memory chips offer the best example of the power of manufacturing mastery. JEDEC standards constrain memory design. You can improve the architecture, you can improve the controllers, and you can improve the interface and packaging. However, the design elements are relatively simple, and many traditional hardware experts continue to believe the leading producers’ current pricing power is only transitory.

But the real bottleneck is not imagination in design. The Armstrong era manufacturing has become so complex that anyone outside the elite group of three has little hope of matching them for years. It is about yield. It is process control. It is the defect rates. It is materials. It is consistency. This is why the cutting edge in memory remains the realm of only three.

Logic chip design is immensely more difficult. It is also immensely more business-critical for most tech giants, which is why so many have embarked on their design visions. Custom silicon is not mainly about cost. The deeper reasons are TCO and efficiency. As Apple has shown for its consumer products a decade ago, and this is far more important in the AI era, control over your own hardware could lead to optimizations and creativity with material impact on the final products. In the end, every custom chip aspirant, whether using an ASIC or a GPU, is forced to look for solutions with cutting-edge foundries and memory partners, just like every cutting-edge consumer or enterprise hardware manufacturer.

Evidence of the Flip

In the Angstrom era, with features like Gate-All-Around, advanced packaging shortages, and critical roles played by cooling innovations, atomic-level precision is driving new stacks, deposition techniques, and stacking methods amid the exploding complexities within UV machines. The manufacturing masters have already seen an attendant surge in margins.

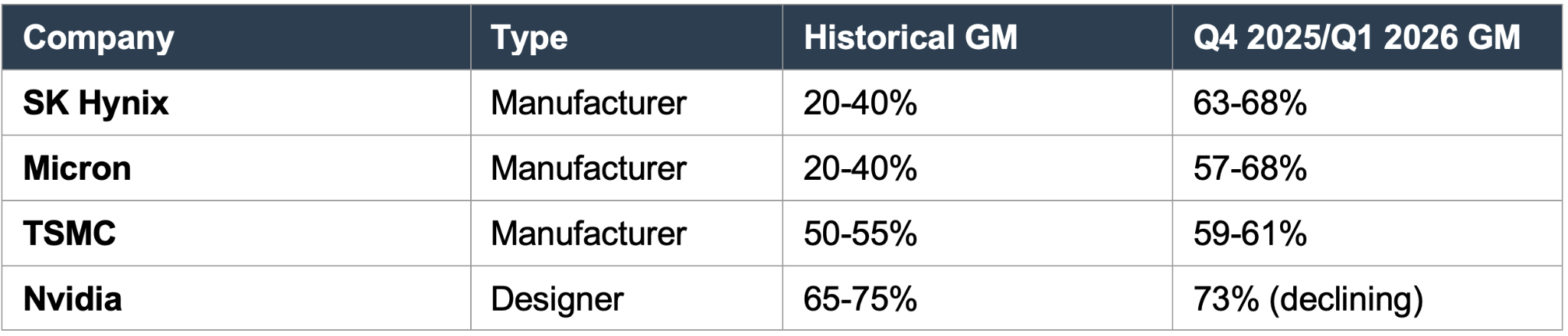

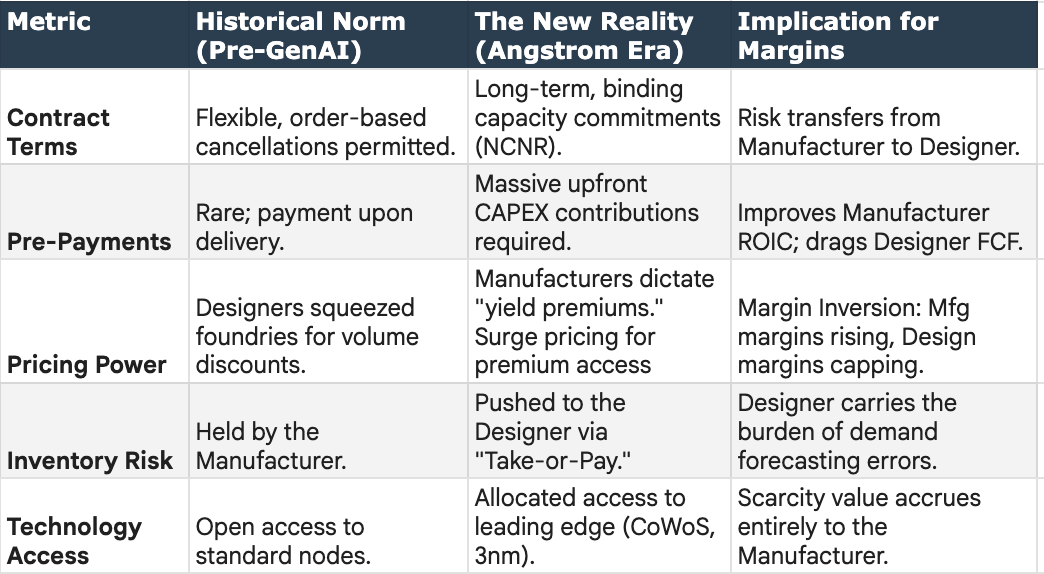

For now, memory producers are surpassing TSMC in gross margins, and all are inching towards the industry-leading numbers historically produced by NVIDIA. The path things are headed is clearer from how contract negotiations are changing.

Memory makers claim they are fully booked for DRAM, NAND, and HBM for 2026. The shortage is forcing the largest players to seek multi-year supply contracts with regular re-pricing. In TSMC’s dated 2024 balance sheet, one witnesses customer pre-payments of around US$9B versus far smaller numbers previously. With manufacturing obligations exceeding US$50bn each from its top two clients, NVIDIA and Apple, the number could be different when the 2025 balance sheet is released.

The Return of the Secondary

For someone writing from an office, running a business at the heart of the tertiary sector, discussing how cognition is getting downgraded almost appears nihilistic. The office segment will remain the world's largest. Many from application, design, content, and similar layers will emerge as winners. Some will be massive winners.

That said, one has to recognise the trends as they appear today. Yes, one should not be cocksure. Caution demands the recognition that the margin evidence is early. The industry is still volatile. But the texture of negotiation is changing, suggesting that what we have witnessed is unlikely to be a fleeting trend over a handful of quarters. Once again, the usual risks of suddenly peaking demand or saturating AI will affect everyone in hardware, with different profiles across companies at different ends.

For decades, the office segments have been everyone's darlings. The tertiary sector. Services. Cognition. Software. The parts of GDP that analysts assume as perennial winners and attendant segments that investors love to own. The secondary sector was for someone else. Somewhere else. But the secondary sector is breaking its silence. The rising power of manufacturing within hardware is not limited to semiconductors. One sees traces in interconnects. In autonomous driving. In robotics. Wherever atoms must be arranged with precision, the balance is shifting. The physical world is reasserting its value over the virtual. If this theme persists, and we at GenInnov have been believers, the relative movements in market valuations may have a lot more to go.