In a pivotal scene from the series WeCrashed, Masayoshi Son sits with Adam Neumann, scribbling an audacious $10 billion valuation on a napkin and urging him to dream "ten times bigger." Such moments often strike fear into traditionalists, signaling reckless abandon and echoing dot-com implosions from decades past. Conventional wisdom suggests this is hubris, the harbinger of collapse.

Yet, the reality is far more intricate. When it comes to fueling substantial growth, capital expenditure, and critical innovation activities, an extremely low cost of equity isn't a symptom of instability, but perhaps the most vital enabler for any society. What appears as a high valuation to a secondary market investor is, for a banker structuring a transaction or a corporate undertaking a multi-year investment program, simply a low cost of equity.

Innovation growth isn't primarily a function of central bank actions and their impact on borrowing costs; the cost of risk capital profoundly shapes it. And critically, it's not merely about the costs or the ability to secure funding, but also the willingness to deploy shares as a currency. At GenInnov, an organization with ambitious technology and infrastructure plans, we are firsthand witnesses to how our most audacious visions often falter due to factors that drive the cost of equity higher in bargain-focused regions outside the U.S.

For those concerned about U.S. valuations, it's the audacious deployment of funding opportunities by its corporations that assures the society's continued leadership in innovation. This holds irrespective of the lack of government funding or inevitable market downturns. U.S. corporates, more than anywhere else, are quick to leverage the current bull market for more than just simple cash raising, offering invaluable lessons for the rest of the world.

The American Fever of Acquisition

Over the last few weeks, the world has watched transfixed as a flurry of major acquisitions and unparalleled talent grabs unfolded across the US tech sector. For many traditional observers, the sheer scale of these transactions suggests irrational exuberance, a hallmark of a market bubble. Yet, what many miss is the strategic brilliance underpinning this activity: the pioneering use of richly valued shares as a "private currency."

Unlike much of the rest of the world, where cash remains king, American corporations, including publicly listed tech titans and not just venture financiers, are quickly and materially leveraging their high valuations to fund growth, acquire cutting-edge technologies, and poach elite talent without draining their cash reserves. Effectively, market levels are enabling large public companies to undertake ambitious growth strategies, both through internal divisions and external acquisitions. The willingness and ability to deploy equity as a primary currency is creating a profound divide, setting the US apart in the global race for innovation.

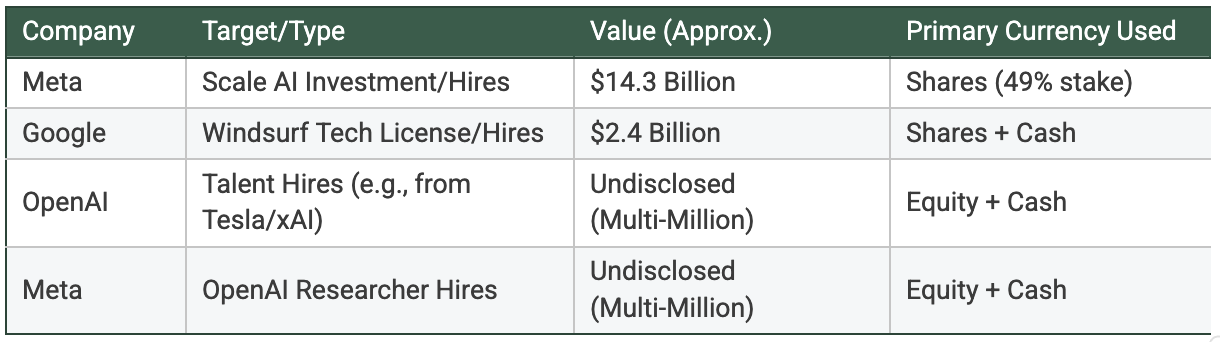

Here's a glimpse into some recent prominent US tech transactions illustrating this trend:

This brief snapshot merely hints at the feverish pace of activity gripping the U.S. tech landscape. The intense rivalries and high-stakes talent grabs unfolding now are so dramatic, they'll undoubtedly inspire countless books, podcasts, and TV series for years to come. In stark contrast to this relentless American dynamism, the rest of the world remains largely silent, marked by little more than conventional IPOs and secondary share sales.

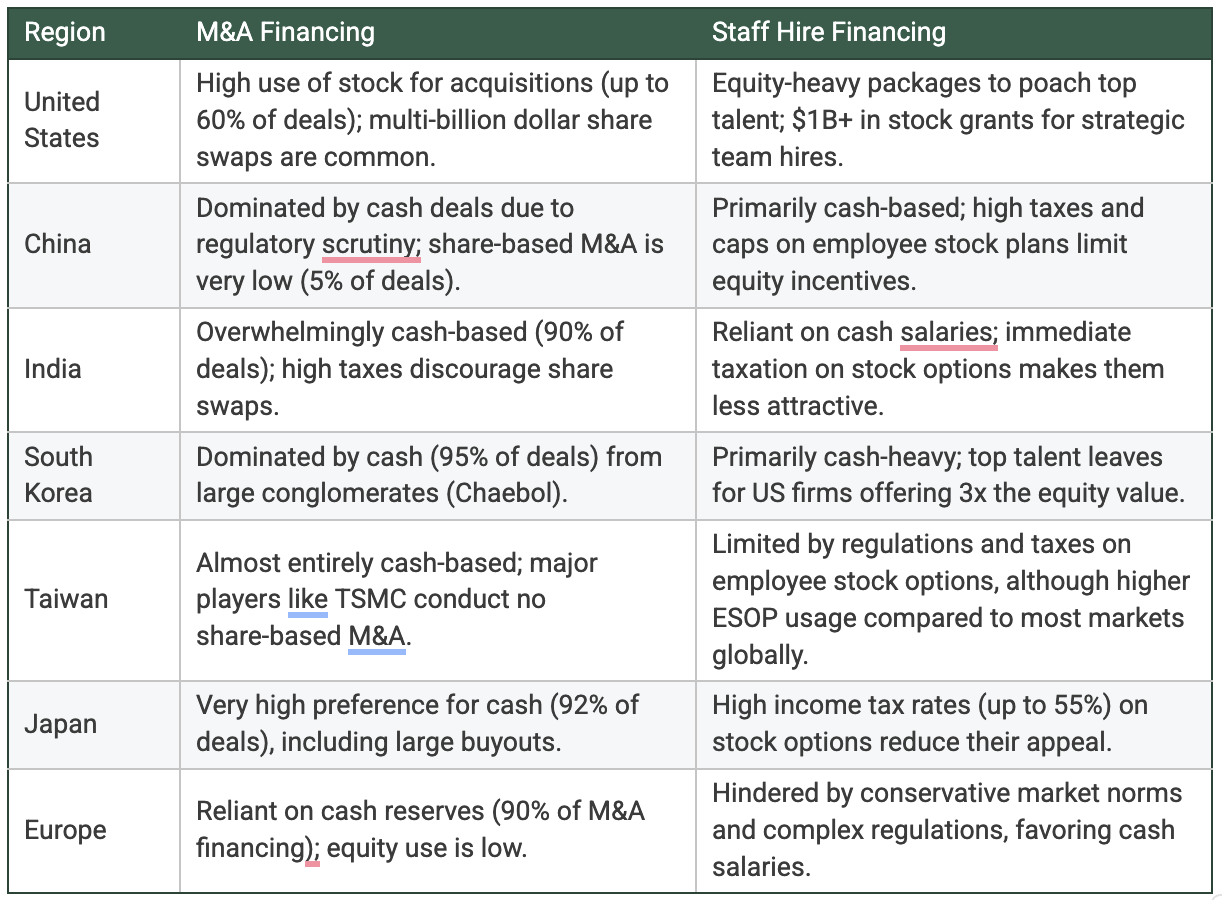

The Valuation Disparity and Share Tolerance

The ability to wield an alternate currency, like a company's own shares, is fundamentally predicated on its valuation—or, more precisely, its cost of equity. For much of the world, a stark reality persists: valuations, whether in public or private markets, are not remotely as high as those in the U.S. This disparity represents a primary, though not exclusive, impediment to replicating America's audacious growth model. Even in markets like India, where specific sectors or individual stocks might boast impressive valuations, both corporate and investor tolerance for the widespread use of new shares for growth-oriented initiatives is markedly lower.

This valuation gap isn't merely a numerical difference; it reflects deep-seated distinctions in investor appetite, risk tolerance, and corporate financial culture. Markets outside the U.S. often prioritize immediate profitability, dividend payouts, or established revenue streams over speculative future potential, leading to more conservative pricing. This financial conservatism, coupled with a general aversion to dilution, means that issuing shares for acquisitions or talent translates into significant perceived cost and shareholder pushback. Without the inherent "cheapness" of equity that high valuations provide, and the willingness to utilize it, companies are forced back to traditional cash-based transactions, severely limiting their scale, speed, and strategic flexibility in the global innovation race.

Creative Financing: Beyond Shares to Compute Power

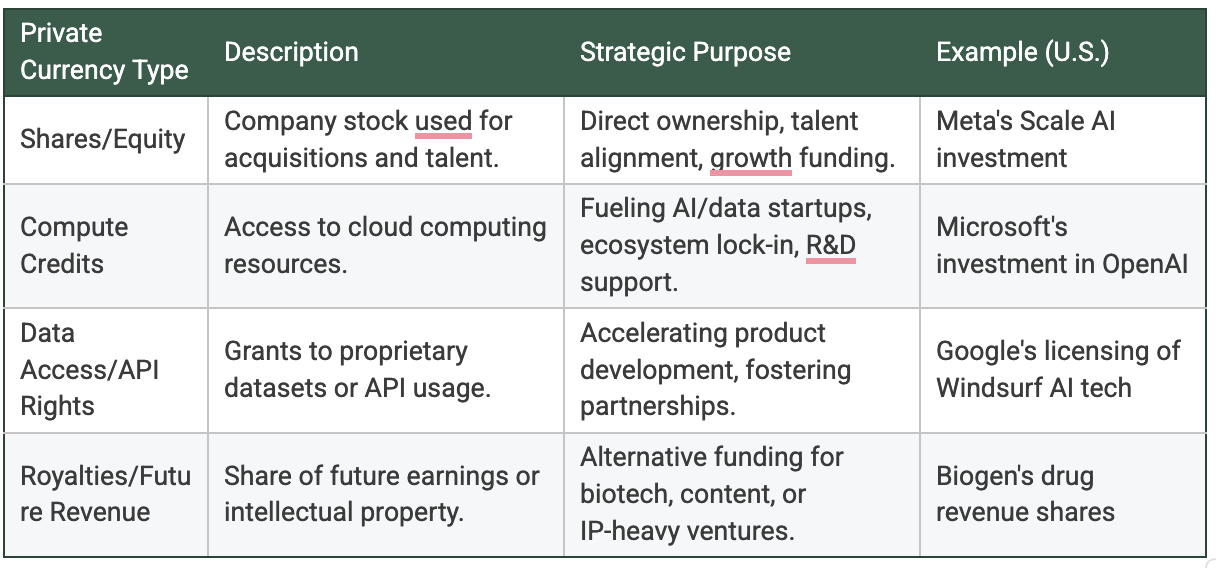

Valuation alone, though critical, isn't the entire story. Equally essential is the corporate creativity that marks American approaches to financing. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in hyperscalers' deployment of compute resources as a non-traditional investment mechanism, starting a few quarters ago. Giants like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google strategically offer cloud computing credits to startups and AI innovators, effectively investing through services rather than direct capital.

Such credits are often seen by purists, including us at times, merely as receivables or deferred revenue, but the reality is far richer. These arrangements provide critical support for cash-strapped innovators, who receive significant resources without immediate financial burden, enabling rapid scaling of ideas. Moreover, this approach locks promising startups firmly within the hyperscalers' ecosystems, ensuring a future revenue pipeline and industry alignment.

US corporations have employed various methods to stimulate investments in their ecosystems, as highlighted in the table below.

The Necessary Folly of Financial Alchemy

Financial innovation is often mocked as alchemy. A derogatory term, conjuring up visions of charlatans turning lead into gold, or worse, turning good money into nothing. And yet, innovation cycles, even the most genuine ones, depend profoundly on such financial wizardry for the funding of the most ambitious projects. For markets conditioned by past busts and bubbles, this is unsettling terrain. Indeed, many traditionalists see articles like this as future museum pieces—ready-made ironies awaiting the next inevitable crash.

They aren't entirely wrong. Innovations, financial or otherwise, rarely emerge unblemished. Excesses will occur; unsavory practices will surface. Over-optimism will lead to misplaced bets, and periods of exuberance will give way to stark reality checks. When markets inevitably correct, some ideas lauded today will seem absurd tomorrow. As the writer himself learned in the harsh school of the Asian Financial Crisis, it's easier—and more immediately gratifying—to mock the follies of optimism during downturns than to praise its courage.

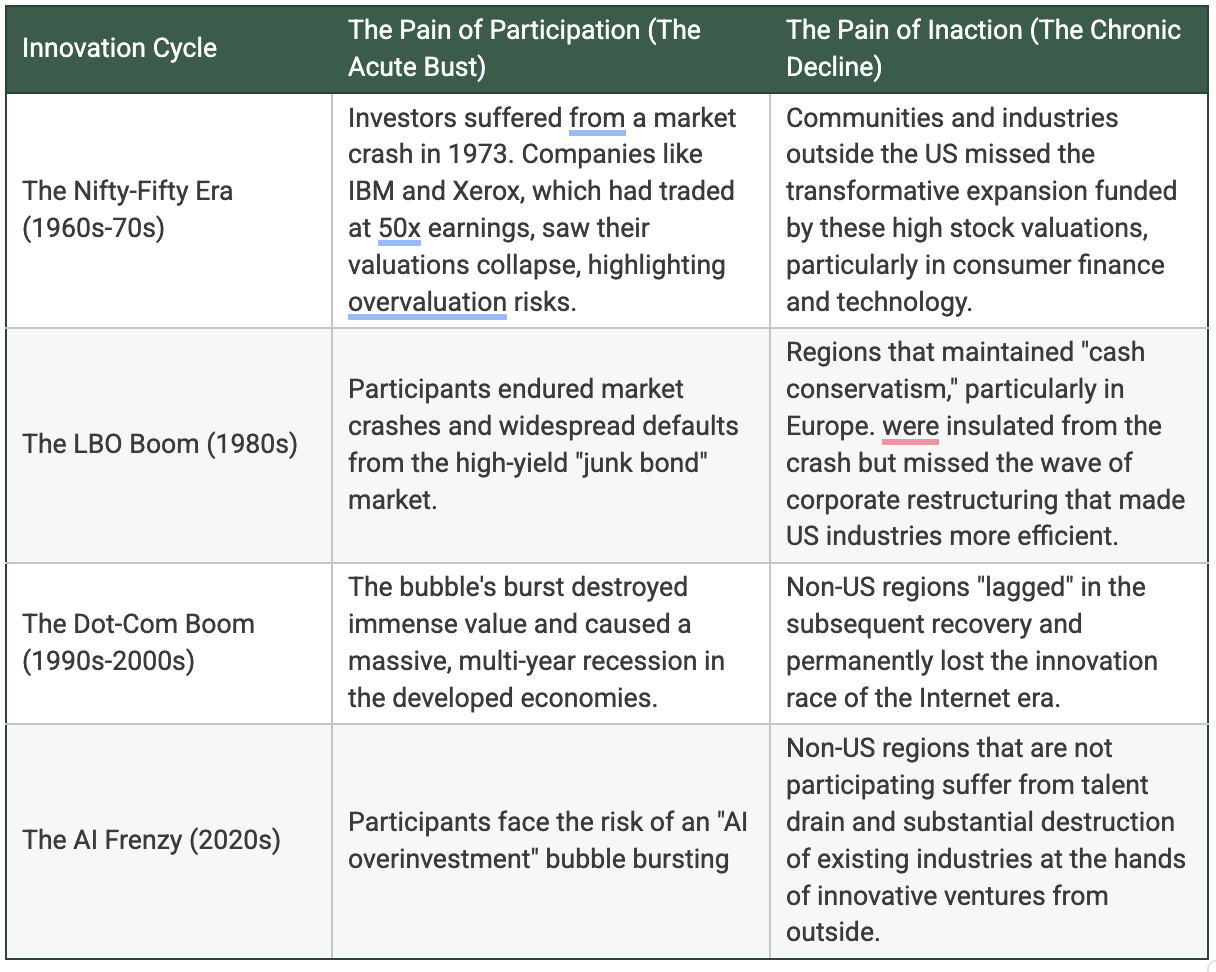

Yet, having witnessed cycles come and go, one uncomfortable truth remains clear: It is far better to endure the periodic folly of bubbles than to exist in a cautious stasis that risks even greater irrelevance. This assertion might seem callous when downturns destroy livelihoods and reshape societies, sometimes permanently. But it’s equally callous to ignore the silent catastrophe of inaction. Those investors and companies that today sit passively, waiting for subsidies, governments, or external events to validate their prudence, are inadvertently placing themselves and many around them in profound peril.

The pace of creative destruction underway dwarfs historical precedents. We strongly believe that the advent of the AI era is causing disruption potential in nearly every industry and activity across the globe. Markets that fail to harness these financial innovations—however speculative they seem today—may never catch up. They risk permanent relegation to economic sidelines, not simply temporary discomfort from an inevitable market correction.

In writing these lines, the irony is clear. The arguments here might soon appear naïve, their writer overly enamored with the possibilities of today, insufficiently wary of tomorrow's cold truths. Yet, perhaps the greatest folly lies not in today's optimism, but in tomorrow’s regret: a regret rooted in opportunities deliberately, and tragically, ignored.

Innovation Is Holistic

True innovation is rarely confined to a single domain. Those who build creatively in technology often think creatively in finance. This is why leading US technology companies are comfortable deploying their own shares, compute power, and future revenues as strategic tools. For those accustomed to more conventional capital structures, these audacious strategies can be challenging to reconcile. Yet, the worst bull markets are the wasted bull markets, particularly when innovation investment has become extremely long-duration capital expenditure.

As we have repeated multiple times over the last two years, the AI era innovation investments resemble long-duration infrastructure projects rather than the quick-turnaround cycles familiar from the Internet boom. The observers of capex in real estate or physical infrastructure rarely begin looking for ROI or IRR even over three to five years, but that has not been the case for investments in many subsegments of technology in the last two decades. Swift returns on capital were possible, and hence became the expectation during the Internet era. Alas! This has already come to an end, which has caused some technology giants to freeze, and many others, such as Meta, to behave differently compared to before.

In other words, many current investments will appear mispriced, illogical, or even reckless when evaluated over short spans of one to five years. Yet from a longer perspective, decades rather than quarters, these commitments could prove foundational. Moreover, some investments, while not yielding direct financial gains for the initial undertakers, can still generate immense societal benefits, laying the groundwork for entirely new industries and capabilities.

The very lifeblood of these long-duration, speculative growth investments is a cheap cost of equity, which is a fancy way of saying high valuations or an optimism-fuelled bull market. Just as infrastructure projects thrive on low-cost debt, the ventures pushing the boundaries of new technologies, where the end result is inherently uncertain, demand the lowest possible cost for risk capital. From the viewpoint of secondary market investors, current valuations might have lost the margin of safety. However, these market levels are a minimum requirement for the type of funding activities necessary for progress.

Indeed, societies burdened by a chronically high cost of equity—such as South Korea, where vested interests sometimes actively resist reforms aimed at lowering equity costs for personal or corporate control reasons—face substantial long-term risk.

This perspective often eludes financial investors who exclusively seek bargain prices and adhere strictly to the principles of value investing. While such investment styles have undeniable merits and foster market efficiency, they can inadvertently depress the values of “currencies”, aka shares, required for funding at multiple stages. Societies burdened with excessively high costs of equity, or those where value or quality investor cohorts dominate, face the tangible risk of falling irrevocably behind in this innovation era. It's not merely about the general market's cost of equity; it's about the ability to secure low-cost equity for companies undertaking ambitious, long-term experimental projects, like a DeepMind or a SpaceX. A low cost of equity for a stable company that neither needs nor seeks capital for growth does little to stimulate critical innovations.

Finally, an economy’s true vitality depends not just on the affordability of equity but critically on the boldness of entrepreneurs to deploy it when outcomes remain uncertain. In the era of big-ticket capex, this boldness is not required of entrepreneurs in the VC space, but rather of those who are the largest. Herein lies America's quiet edge: an unmatched willingness to translate low equity costs into active, audacious risk-taking even amongst the giants.