Unlike energy, wealth can be created or destroyed in thin air. As we witnessed with Bitcoin’s crash last Friday on thin volumes, notional wealth can evaporate in moments. This fragility stalks every market, heightened by geopolitical uncertainty and crowded, one-directional trades. When the tide turns, as it always does where the currents are most pronounced, it will create violence.

And yet. The single greatest certainty of our time is the one we are taught to ignore. After the fall, after the fear, after the headlines scream of ruin, there is always a tomorrow when it will be policymakers’ time to react. This truth, which will more likely define what endures, is more important to remember than the anxious wait for the crashes for all wishing to be long-term investors.

We live in an age where ideology has surrendered to immediacy. No one wants to be Volcker or Thatcher. No one wants to be the adult who stops the party. Every central banker, market regulator, and politician in charge of government finances speaks of prudence but acts out of fear. Fear of recession. Fear of market panic. Fear of being the policymaker remembered for breaking something real in pursuit of something abstract.

This is not a hopeful platitude. It is the central, unwritten doctrine of modern power. It is the operational code of the 21st-century economy. We are raised on fables of financial gravity. We are told that bubbles must burst. That every boom must be paid for with a bust. That the system, in its wisdom, must periodically cleanse itself with fire. This was the world of our textbooks. It was the world of iron-willed policymakers, idolized in our history books, who saw recessions not as tragedies but as necessary medicine.

We have entered a new paradigm. The violent collision of two forces defines it. The first is a technological revolution rewriting the rules of human endeavor. The second is a new class of policymaker, stripped of ideology, whose only remaining belief is that the system must not be allowed to fail. One can theorize that they may not always succeed, but it is more important to note that they will keep trying and doubling down when failures persist. The greatest risk of betting on a crash is blindness to recognizing the inevitable resistance.

The Self-Funding Flywheel

The old business of money was a bridge. A bank took capital at a low cost. It lent that capital at a higher cost. It profited from the spread. For centuries, this arbitrage, built on trust and tangible assets, was the engine of commerce. That engine now sits in a museum.

A machine of pure abstraction powers the new economy. It is a self-funding flywheel. And its fuel is belief. This machine begins with a valuation. Or, the cost of equity in the previous era’s parlance, which would make more sense when discussing policy implications. In the old world, a company’s value was a consensus, hammered out daily in the broad, liquid arena of a public market. In the new world, value is a pronouncement set in a private round by the single most optimistic investor. The highest bid does not win an auction; it anoints a reality. A valuation is imparted on paper, in a market of one, creating a synthetic high-water mark for the entire enterprise. This number, conjured in a boardroom, becomes the company's "low cost of equity." It becomes a currency more potent than the dollar.

Once minted, this currency is weaponized. Its applications are a masterclass in financial alchemy. First, it is used in the classic arbitrage of the 1960s conglomerate mania. The high-valuation company, flush with its richly priced paper, acquires businesses with lower, more reality-based valuations. For decades, we have also witnessed how shares could be used for payments, not just as incentives to employees but even to vendors.

An application that is becoming a hallmark of our era is the way valuations are used to manufacture revenue. This is the flywheel's most elegant and abusive gear. The company invests in another firm. The condition? The smaller firm must use the investment capital to buy the larger company's products. Capital flows out as an investment and flows back in as revenue. No cash-based transactions may have occurred, yet the top line grows without an increase in payables for one, and valuations grow along with the availability of needed products without an increase in payables for the other. The growth justifies a higher valuation. The higher valuation allows for more such investments.

This has been the quiet engine of the technology sector for some time. But the sheer, eye-popping scale of deals like the one in the OpenAI-AMD ecosystem represents a new stage of audacity. It is a closed loop of manufactured growth, an accounting Escher sketch where the stairs lead only back to themselves. It is the moment the quiet part was said out loud. These looped transactions are now the talk of the town, leaving even optimists speechless.

So, what happens when such deals begin to crumble under their own weight? We see no policymakers rushing to stop them. But markets can and do fall for other reasons. A sudden spike in the cost of equity could trigger a vicious, self-reinforcing cycle of collapsing valuations and frozen investment. Wouldn’t this cause lasting damage, echoing for years? Wouldn’t it be the great reversal that doomsayers predict? The classical answer is to flee, wait for the carnage to consume the era's worst offenders, and return years later to pick through the wreckage.

In a World Without Purists

In another age, the answer would have been a resounding "yes." A Volker or a Bagehot would have named it excess and drained its oxygen. Or, a Hayekian would have let it burn to clear the underbrush when the fire began. A collapse of these self-funding flywheels would have been seen not as a disaster, but as a necessary and righteous purge. It would have been welcomed by some in the policymaking.

The world, until the recent era, was ruled by ideologues. Or, paraphrasing Keynes, these were practical men who believed themselves to be exempt from intellectual influence, but were still slaves of some defunct economists. They were men and women who saw economic policymaking not as a matter of management, but of morality.

Men like Andrew Mellon, who, after 1929, advised President Hoover to “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers.” He believed in the cleansing fire. In Germany, the Bundesbank, haunted by the ghost of Weimar-era hyperinflation, would impose punishing interest rates on an entire continent to defend the sanctity of its currency. In Britain, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher waged a decade-long war on her own industrial base and unions, accepting mass unemployment as the necessary price to break the country's inflationary fever. Even in the technical world of accounting, regulators like Sir David Tweedie championed mark-to-market rules, an ideological crusade for absolute truth on the balance sheet, even if that "truth" amplified a financial panic.

Such a figure could not exist today. The modern policymaker is a pragmatist, not a purist. They are trapped by a new set of commandments that make allowing a true, cleansing crash an impossibility. First, the geopolitical imperative. The rise of artificial intelligence is this century’s Cold War. No government can afford a decade of credit contraction and corporate collapse while its rivals accelerate. A deep recession is no longer an economic policy choice. It is an act of unilateral technological disarmament.

The second is the wealth effect mandate. The modern economy rests on asset prices. Pension systems, sovereign funds, and political donors are all tethered to valuations. At the margin, job creation is far more linked to market levels than interest rates. The same is true for government finances. A market collapse is no longer a cyclical event; it is a mass default of faith, a fracture in the social contract with consumers and savers, employment-seekers and government subsidy dependents, those who voted for stability, and those who sought protection.

The third is the symbiosis of power. The architects of this new “equity money” are the largest corporations on earth. They do not lobby; they legislate. They shape standards, define accounting treatment, and co-write policy drafts that guard their own valuations. Regulators and politicians move in concentric circles of mutual dependence. The governed and the governors own the same ETFs!

Therefore, whenever vicious cycle risks emerge, when the cost of equity spikes and valuations spiral downward, the question is not if the pragmatists will intervene. The question is how much and how soon. If the cleansing fire is forbidden, then the only option is to flood the forest. But the nature of the flood must match the nature of the fire. The intervention cannot be a simple repeat of 2008. The disease has mutated, and so must the cure.

The Evolution of the IOU

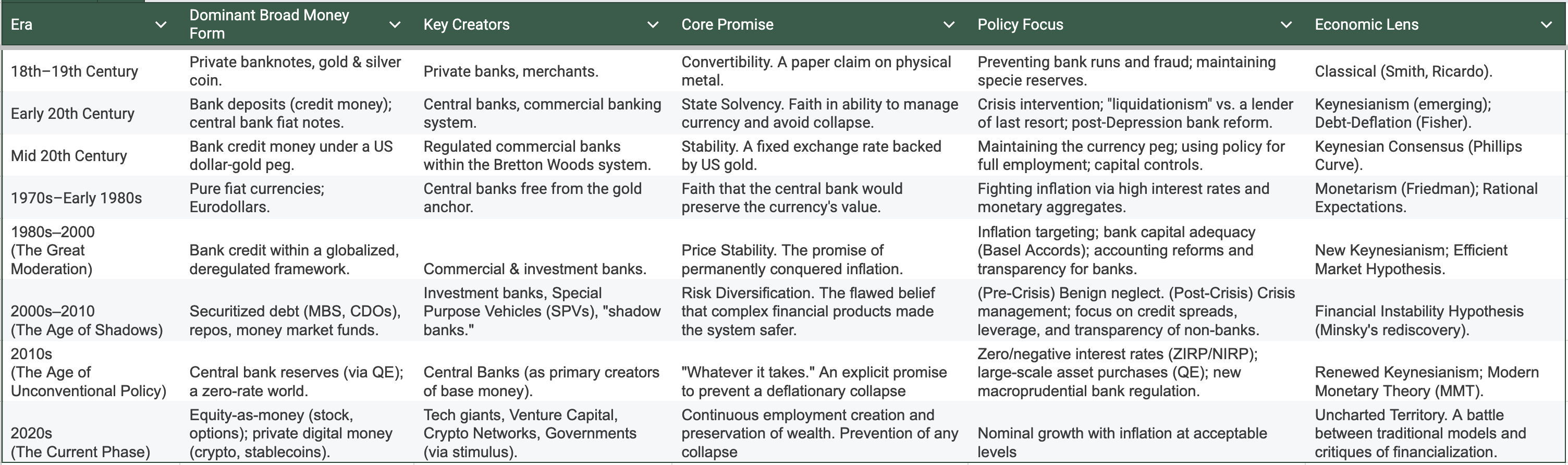

To understand the form the next reflation will take, we must understand that the very substance of money has transmuted. The policy response to a crisis is always tailored to the dominant form of money that is threatened. A crisis of private banknotes in the 19th century demanded a lender of last resort. A crisis of bank credit in the 1930s demanded deposit insurance. A crisis of securitized debt in 2008 demanded the purchase of mortgage-backed securities.

Today, the frontier of the economy is not funded by bank credit or securitized debt. It is funded by Equity-as-Money. When this system comes under pressure, the intervention cannot be limited to cutting interest rates or shoring up the banking system. The support must be aimed directly at the heart of the new machine: the cost of equity. The policy goal will be to directly support valuations when the need arises.

The table below is not just a history of money. It is a history of crisis response. Each era’s unique form of "broad money" dictated the unique form of its eventual bailout. The final row is not a history; it is a prophecy of the tools that will be deployed next (readers may need to zoom in to read the table captured in the image. The table displays how monetary history has changed and why each phase has led policymakers to take steps unforeseen by previous generations. This will be the case when the need arises next time.

The Bubble on Bedrock

It is tempting to look at this world and see only a bubble. A grand illusion. A Ponzi scheme of unprecedented scale, awaiting its inevitable reckoning. This is a comforting thought for those who feel they have found the shelter. It is also a profound misreading of the moment.

This is not a bubble about nothing.

The financial superstructure is fantastical. The valuations are stretched to the point of absurdity, at least in some corners. But the technological foundation is granite. The change is real. From a standing start just a few years ago, AI models now process quadrillions of tokens of information a month. This is not a forecast. It is a measurement of a new industrial reality. It is an explosion of machine cognition that is rewiring our world. It is happening in the server farms of Virginia and the factories of Shenzhen.

This is the great paradox of our time. We are funding a genuine, world-altering revolution with a financial system that increasingly resembles a fantasy. The excesses are real, but so is the utility. It distinguishes this era from the Tulip Mania or the South Sea Bubble. Those were bubbles of pure psychology. This is a bubble built on bedrock.

Sure, there were bubbles surrounding massive innovations that went bust. But at no time was the change so rapid, so critical in timing and geopolitically sensitive that those in charge could allow a period of economic cleansing for a more sustainable future. One can paint a scenario of geopolitical turmoil or changed social or political priorities where the reversal of excesses turns uncontrollable, but that’s not where the evidence points today.

Living in this world requires a new catechism. The old virtues—prudence, thrift, a cautious fear of debt—are irrelevant for now. The old wisdom—to wait for the crash, to buy when there is blood in the streets—assumes that the authorities will ever again allow blood to fill the streets for a prolonged period. The unsavory consequences—grotesque inequality, the erosion of moral hazard, financial repression that allows today’s excesses to dwindle without the perpetrators suffering commensurately—are considered acceptable costs to prevent the alternative.

One does not have to like this world. One can find it ethically and economically monstrous. But one must see it for what it is. The doomsayers are not wrong about the symptoms. They are wrong about the unraveling paths or when they denigrate the changes afoot to create better justifications for a deep and long crash. If they are not waiting for a purist to arrive and burn it all down, they implicitly forecast policy action that cannot stop the conflagration. While the risks of the worst cases exist, the higher are the risks of assuming this music is going to stop.